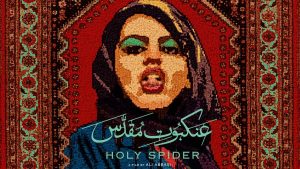

Based on the true story of Saeed Hanaei, a man who murdered 16 female sex workers under a religious pretext of ‘cleansing’ his city of sin, I recently (finally) watched the often brilliant Iranian filmmaker Ali Abbasi’s Holy Spider, released back in 2022. The film follows a fictional journalist, Rahimi (played by Zar Amir Ebrahimi), who travels to the holy Iranian city of Mashhad to investigate the murders. Her visit is met with institutional bureaucracy, suspicion, police threats, support for the killer, and systemic misogyny. There are exceptional performances from all involved, but the role of playing the killer’s wife struck me as one of the most interesting and indeed, maybe one of the most difficult parts to master. It was a role that stood out and one that led me to the actor who portrayed the character brilliantly.

Forouzan Jamshidnejad is a Norwegian-Iranian actor who plays the role of Fatima in Holy Spider, the wife of our serial killer in the spotlight. She began her career in the arts at the age of five and has since gone on to star in Iranian plays, TV, and made her feature film debut in 2021 with Mitra. Yours truly at Felten Ink had the pleasure to speak with Forouzan about her role, how she approached such a character, the backlash she would face for doing so, what drew her to start her career at such an early age, her activity in promoting freedom of expression and democracy in Iran, and the challenges that continue to face women in the country. We also detail the future of Iranian cinema, its key filmmakers, and, lastly, her love of painting…. You must balance the light with the dark.

Dear Forouzan, you started your acting career early, at the age of five? Can you tell me what prompted you so early on, and what kind of roles?

I often think that I did not choose theatre and acting — it chose me, and entered my life. At an age when I couldn’t even read or write yet, I found myself stepping onto a large, dreamlike stage full of colour, light, and dialogues — many of which I didn’t even understand at the time! And I must say, from that very first moment, I was enchanted by this art form. We grew up together, hand in hand. One of my relatives led a theatre group in the cultural centre where we lived. The entire group consisted of adults, and I was the youngest member. When I was five, they gave me the role of a little pigeon in a musical play. The dialogues and songs had been recorded on cassette tapes, which my mother played for me at home. I memorised them simply by listening — and that was how I began. The stage quickly became like a second home to me. On it, I could be free — I could sing, dance, speak, even play. Sometimes, during performances, the older members of the group would have to quickly escort me backstage because I needed to go to the bathroom! The freedom I felt on that stage as a child is something I still carry with me every time I step into a role.

So, I sense this type of career has always been part of ‘your being’?

Yes, I do feel that this career has always been a part of me. It’s interesting that you sensed it, because I feel the same way. That early connection to the stage gave me not only a deep sense of freedom but also a sense of security that became part of me from childhood. I learned not to fear the presence of the audience — I became accustomed to hearing their breath, to feeling their subtle movements, to sharing the space with them. Over time, the stage became a space of trust and connection for me — and that feeling has remained ever since.

What kind of influence did your parents have concerning your innate creativity and desire to act and be onstage?

My mother had a deep passion for acting when she was young. In her teenage years, she began to pursue it professionally. At that time, she and her family were living in Khorramshahr, a city in southern Iran. Then the war between Iran and Iraq broke out. My mother and her family lost their home during the bombings, and they became displaced. In those days, there was no real support for families who had lost everything, so they were forced to move and rely on relatives in other cities. My mother left behind not just her home, but also her dreams. And in a way, the part of her that was never able to fulfill that passion came alive in me. She always supported me, together with my father. I must say my father played an important role as well. At that time, many families didn’t want their daughters to be involved in theatre groups. I remember that when I was a teenager, two of the girls in our group had to attend rehearsals in secret. One of them even had to stop coming after her brother found out. I still remember one hot summer afternoon during a rehearsal — her brother came and took her away violently. I was fortunate. My parents allowed me to follow this path freely, and their support gave me the strength to continue.

What was life like for you, or women in general who wanted to have a career in the arts?

As a woman pursuing a career in the performing arts in Iran, I faced many restrictions — just like so many other women artists of my generation. Theatre, being a public and visible art form, was constantly under the scrutiny of the state’s censorship apparatus. We were either resisting it or forced to comply. And this system didn’t just limit our artistic work — it reached deep into our personal lives as well. The most painful part was knowing we were never allowed to show the real life of Iranian people — especially the depth and complexity of Iranian women. We were expected to follow a rigid, often hypocritical image of women designed by the authorities — an image that had little to do with reality. Female performers were required to cover their hair and body at all times — even in scenes where the character was alone in her bedroom. I remember playing characters who were mothers, lovers, or daughters, and yet I wasn’t allowed to touch the male actor — not a hug, not holding hands, not even a realistic physical fight between a couple. A mother couldn’t embrace her child after months of separation. Two lovers couldn’t touch. These rules weren’t just strict — they were dishonest. And we all knew it. Still, we were expected to speak and act within that lie. I was repeatedly warned during performances simply because a bit more of my hair was visible. Officials from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance would frequently attend our rehearsals to enforce religious and political “red lines.” Another particularly painful restriction was around scenes of joy or celebration. Whenever music played or a festive moment appeared in a film or performance, only men were allowed to move freely and dance. Women had to stand politely at the side, clapping quietly and gracefully. We were present, but never fully part of the joy — always watching from the margins. That repeated exclusion left a deep mark on us. As Jafar Panahi once said in an interview, “You always have to navigate between what can be said and how to say it.” And that’s exactly what it was — constantly worrying about what you can’t show, or how to show something so that it remains unseen. It was exhausting. And it was layered. But it wasn’t just the visuals or the body that were policed — women were erased from stories themselves.

“After the Islamic Revolution, female characters in Iranian cinema became passive and one-dimensional: obedient wives, kind sisters, jealous daughters. They had no agency, no ability to shape the drama they were part of. Some directors resisted this. Bahram Beyzaie was one of the few who gave women power, presence, and complexity on screen. His collaborator, the brilliant actress Susan Taslimi, brought those characters to life — but was eventually banned from acting and appearing on screen, and has lived in exile in Sweden for years.”

What about today?

The regime continues to suppress and distort the presence of women in art — as if the Iranian woman must remain a symbol of quiet modesty, stripped of agency and depth. Abbas Kiarostami, facing similar restrictions, found creative ways to work around them — often choosing to depict women outdoors rather than inside the home, to avoid the forced display of false veils and constructed behaviors. More recently, with the rise of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, many women artists have refused to remain silent. Some of the most respected Iranian actresses have been banned from working because they stood in solidarity with the women and girls of Iran — declaring they would no longer hide the truth or act under mandatory hijab. They were summoned for interrogation; some detained, others confined to their homes. But their voices have not been silenced. In the end, we were — and still are — moving through an invisible prison, trying to speak truth in a space that punishes honesty.

And your decision to leave?

My decision to leave Iran was not a simple one — it came from a complex mix of reasons. I have always had a deep emotional bond with my country, and in many ways, I still do. But as a woman, I constantly had to struggle with restrictions that shaped every part of my personal and professional life. Eventually, I was forced to leave, and I have been deprived of the right to return to my own country ever since. Due to my artistic and personal activities, I now face legal threats from the Iranian judicial system.

I understand you’re now living in Norway – Can you speak more about that need for change and how it’s affected your career, for the better?

To be honest, after migrating to Norway, acting gradually began to feel like a distant and unreachable dream — a part of my past that I felt increasingly detached from, as if it were fading away. At that time, Iranian diaspora cinema hadn’t yet come to life the way it has today, and due to language barriers — and honestly, dealing with post-migration depression — I didn’t see a place for myself in Norwegian theatre or cinema. I tried to fill this void through other creative avenues — painting, writing, and editing. I wrote articles and cultural reports for BBC Persian, worked as an editor for the film magazine Cine-Eye, and even edited two books related to cinema. During one of my reporting trips to a film festival in a Norwegian town, I met Zar Amir Ebrahimi. A few years later, she invited me to act in the film Mitra, and afterward, she introduced me to Ali Abbasi, the director of Holy Spider. Zar played the lead role in Holy Spider and also worked as the casting director for the film.

Which brings us nicely onto Holy Spider and working with Ali Abbasi…

Working with Ali Abbasi was an incredible experience — especially because I had previously been deeply moved by his earlier film Border. Now, regarding the role of Fatima in Holy Spider: it was truly a turning point in my acting career. For the first time, I was able to fully reclaim my identity as a woman and as an actor — and perform without any artistic restrictions.

Holy Spider was indeed where I came to see your work, which I thought you were a standout in. How did you approach such a role, the wife of the killer?

Fatima was a multi-layered and complex character, very different from me in real life. She was a traditional, conservative, and religious woman, shaped by a deeply male-dominated society. She also spoke with a regional accent from the city of Mashhad — where the real story took place — an accent I was unfamiliar with, which meant I had a lot of work ahead of me. But I loved Fatima — because she allowed us to see hidden and unexplored layers of religious women in Iranian society. Her body, her hair, her intimacy and expressions of desire — these were aspects never shown in Iranian cinema. That, in itself, was an act of breaking taboos — and I feel deeply proud to have taken part in that. Of course, that came with a cost. After the film’s release and its wide distribution, I was subjected to intense hatred and insults online, especially from religious conservatives and cyber-armies aligned with the Islamic Republic. And to this day, it still occasionally continues.

I find it shocking that you got hate from your performance, for what reasons I cannot register. Your character is still admirable in my opinion.

To be honest, playing the role of Fatima was a deep confrontation with parts of myself — emotionally, ethically, and even politically. I had to portray a woman who, on the surface, is devout, obedient, and composed, but inside, she’s filled with fear, doubt, and contradiction. Fatima is unaware of her husband’s crimes until his arrest, but once the truth comes out, instead of cutting ties or resisting, she chooses to defend him. This wasn’t a naive or thoughtless decision — it emerged from a system that trains women from childhood to obey, to remain loyal, and to stay silent in the face of male authority. For me, the most challenging part was portraying a woman who justifies her husband’s crimes not only to herself but also to her children — insisting that their father had acted “in the name of God,” to “cleanse society of vice.” At that point, I had to force myself to look away from the truth and step into a mindset that, while terrifying, is all too real. A mindset still present in today’s Iran — women who participate in the repression of other women. Dressed in the uniforms of the morality police, or defending a regime that criminalizes women’s bodies. This reality culminated in the death of Mahsa Jina Amini, killed by the morality police simply because a few strands of her hair were showing. Her death sparked a powerful women-led revolution. While playing Fatima, I felt I wasn’t just portraying a wife — I was embodying a mentality, a structure that turns women from agents of change into instruments of oppression.

What part does religion still play in your life since leaving Iran, and is it important to you? Please explain to a Westerner who has no faith in his own life?

Religion, for me, has always been a layered and evolving concept. I grew up in a society where religion was everywhere — in schoolbooks, on television, on the streets, and especially in women’s lives. But what was presented as religion often felt more like control — a tool used to police our bodies, silence our voices, and dictate how we should live, love, express, and even dream. As I grew older, I began to separate faith from imposed religiosity. I respect belief as a deeply personal and spiritual experience — but I have always resisted when belief turns into ideology, and ideology turns into law. In my personal life today, I don’t follow a particular religion. What matters more to me is ethics, compassion, and the freedom to choose how to live — especially as a woman. I’ve seen too closely how religion, when misused, can rob people of their agency, particularly in Iran, where it’s tied to political power. So no, religion is not important to me in the traditional sense. But the struggle for spiritual freedom — for dignity, for the right to question-that — is deeply important to me.

Ali Abbasi and Jafar Panahi are two Iranian filmmakers I adore. For someone like me in the UK, can you explain what challenges there are for these filmmakers and other artists to work in Iran? (I’ve never visited but would love to)—I know Jafar has had various problems (house arrest, etc) with his work.

For filmmakers and artists in Iran, the challenges are both numerous and, at times, invisible. First and foremost, they must constantly contend with state censorship. Scripts must be approved by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance before production begins. The same goes for casting, costume design, and even the final cut of the film. And yet, many films—despite clearing all these steps—are banned without explanation. You’re always walking on a minefield of red lines—lines that are vague, ever-shifting, and harshly punishable. These include political, religious, and social boundaries that have no clear definition, but crossing them can have severe consequences. Jafar Panahi is a clear example of resistance to this system. For years, he was banned from filmmaking and placed under house arrest. Still, he continued to make films that deeply moved audiences around the world. In the end, his resistance paid off, and the world saw: in 2025, he won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Following the nationwide protests in Iran under the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom”, a deep rift emerged within Iranian cinema. Many filmmakers stood with the people and resisted state pressure, while others chose to remain within the official framework. This divide has split Iranian cinema in two. Inside Iran, a new wave of underground cinema is rising—films that reject imposed censorship and, despite all obstacles, create bold and truthful narratives. One example is My Favorite Cake, directed by Maryam Moghaddam and Behtash Sanaeeha; both directors are currently banned from leaving the country and face prison sentences simply for portraying the love story of a middle-aged woman. Or Mohammad Rasoulof’s film, which, despite intense pressure, succeeded in becoming Iran’s submission for Best International Feature Film at the Oscars. Today, Iranian cinema stands at a historic crossroads: to either remain within the state’s boundaries or to join a cinema that is independent, honest, and willing to take risks.

As well as your work on screen, I noticed you also paint, which is aesthetically pleasing and beautiful. Where do you draw inspiration from in your artwork?

Honestly, my paintings come from within — from my visual memory, emotions, dreams, and personal fantasies. They are not based on a specific concept or theme; they emerge instinctively, often as a way of processing what I feel or remember. And I must say, a woman has always been the central figure in my paintings — not as a decorative element, but as the heart of the narrative. Through her, I express my inner worlds, untold stories, and emotional layers — both as a woman and as an artist. What always amazes me is how, with the patience and time that painting requires, a character gradually takes shape and comes to life. My paintings become alive — and they stare back at me.

What inspires you the most?

What inspires me the most is the complexity of human beings — especially the emotional contradictions that live within us. I’m deeply moved by moments of vulnerability, silence, and the things we feel but can’t easily put into words. Life, the body, memory, and the inherited pain of women shape much of my creative work — whether on stage, on screen, or in my paintings. I’m also inspired by resilience — the way people continue to live, love, and create despite oppressive circumstances. Nature, childhood memories, and dreams often find their way into my imagination. Inspiration, for me, rarely comes with noise — it arrives more like a whisper. And of course, my dreams, with their images and feelings rising from the subconscious, are an inseparable part of that source of inspiration.

What are you currently working on in film/ or anything else artistically?

I’ve worked on a feature film that is now awaiting release. In the coming days, I’ll begin shooting a new film in which I’m acting. At the same time.

Forouzan, it’s been an absolute joy to hear from you. Thank you, and I shall continue to follow your work. Stay tuned for part 2.

Forouzan Jamshidnejadn on social

Read more interviews like this right here on Feltenshaum INK

AND NOW A WORD FROM OUR SPONSOR, KIND OF….