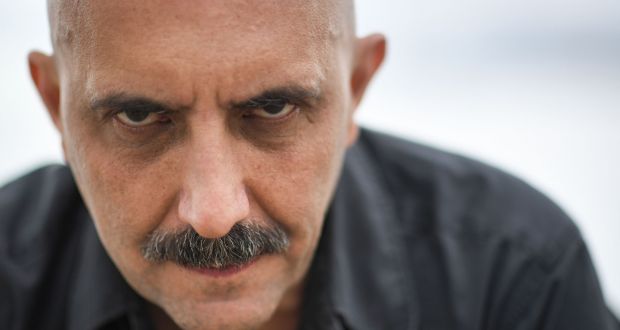

Gaspar Noe is a dangerously provocative and mind-bending filmmaker who has the ability to combine almost every element of what makes truly great cinema. In his own words, he’s already made many films that have, “scared people, turned them on, or made them laugh.”

I would also add that he’s also managed to bore us, or maybe just I, to tears (his 3-D porno ‘Love’), induce horrifying and at times euphoric anxiety (‘Climax’), make most of us switch off at notable and world-famous rape scenes (‘Irreversable’) and in his first and one of my favorite film of his, (I Stand Alone), create an extreme and brilliantly nihilistic tale where even he himself appears to recommend that viewers watch at their own discretion.

With his new film ‘Vortex’, Noe evolves further. He suffered a brain hemorrhage in 2019 and published images of his time in hospital on his Instagram profile – which I initially thought of as a hoax, such is his (apparent) dark sense of humour. The result of recent trauma is ‘Vortex’, a film about an aging couple in decline which stars legendary horror director Dario Argento in the main role of a man dealing with dementia. Here, Gaspar Noe discusses themes of ‘Vortex’, where it came from, and his own sense of decline.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ahTWUQ2R5Q8

Mr Noe, what was the origin of Vortex?

I’ve been wanting to make a film with elderly people for several years. With my grandparents, then with my mother, I realized that old age involves very complex survival issues. It generates overwhelming situations in which those who have protected you most revert in turn to their childhood. So I imagined a film with an extremely simple narrative, with one person in a state of mental deterioration losing the use of language, and her grandson who has not yet mastered it, as two extremes of this brief experience that is human life.

I would say that it’s your least provocative, least violent film to date. Fair comment?

That’s not for me to judge. While it’s my first feature film for all audiences, I’m also told that – due to the very common situation it describes, which most people are or will become familiar with – it’s the toughest. I’ve already made films that scared people, turned them on, or made them laugh. This time I wanted to make a film that made them cry as hard as I could cry, in life as at the cinema. Tears really do have a sedative effect when they come into contact with the membranes of the eyelids, which makes them one of the most pleasurable substances there is. Also, this isn’t the first time that I’ve filmed with the greatest love people older than me: it was the case with Philippe Nahon with whom I made Carne and I Stand Alone. But this time, Vortex is really inspired by recent experiences in my life, and all those ultra-brilliant loved ones whose powers of thought I saw decay and then die before my eyes. The film probably refers to the emptiness that surrounds us and in which we float. I’ve also been told that it recalls Enter the Void in the sense that its subject is the great emptiness that is life and not death.

Perhaps it’s also your most radical, desperate film?

Maybe, in any case not very Manichean. It’s just the story of a genetically programmed disintegration when the whole house of cards collapses. As we wrote for the Cannes Film Festival synopsis: Life is a short party that will soon be forgotten.

Did you write this film following your sudden brain hemorrhage?

No, not at all. I’d already thought about the subject for this film long before. On the other hand, with this stroke, from which there was very little chance that I would emerge alive or unscathed, I was catapulted onto the dark side of the moon. While I was on morphine for three weeks, I thought about my death and its consequences for all those around me, the mess I would have left behind. That’s death: the objects of a life you leave to others and that disappear in a garbage truck as quickly as memories that rot along with the brain. In any case, since the hand of destiny gave me some joyful extra time, I feel that I’m more serene with these two concepts we call life and death. In addition, the convalescence that was imposed on me, followed by this fabulous collective experience of confinement linked to a virus, allowed me to spend months discovering the greatest melodramas of Mizoguchi, Naruse and the unjustly forgotten Kinoshita, whose melancholy, cruelty and aesthetic inventiveness reminded me what truly great cinema could be.

Was it a commando shoot?

I wrote a 10-page text, that grew to 14 pages when I expanded the bodies of the characters to deposit it at the CNC (laughs). Canal + committed and I got the ‘avance sur recettes’ (advance on receipts) for the first time. I shot in April, over 25 days, and finished on May 8th. I had an editing room on set and, since we didn’t have very long shooting days, I started editing right away, in the evenings, on weekends. It was very fast, especially the post-production before Cannes, but I love speed. It worked well for Fassbinder, it worked well for all the great Japanese directors in the 60s. Why do slowly what you can do quickly?

When did you have the idea for the split-screen?

The story of the film is very commonplace, it’s just something that happens quite naturally for people aged 80 and over that their children must manage. And these situations are so heavy day-to-day that most of those over 50 carry them like individual curses that they’re almost ashamed to talk about. For the form, I envisaged something almost documentary, without written dialogue, and on a single set, as realistic as possible. The only aesthetic position I took was to film some scenes in split-screen to emphasize the shared loneliness of this couple, but I hadn’t planned to do so over the entire duration of the film. The first week I only shot a few sequences with two cameras, but in the editing room I realized that when one of the characters left the frame, leaving us alone with the other, I really wanted to continue to see what he or she was doing at the same time. Reality is the sum of the perceptions of those who make it. And since there’s nothing more boring in cinema than this artificial tv movie language that almost everyone uses I thought, as long as we’re making something as contrived as a film, why not have fun with the split-screen? So I timed the shots and filmed the missing parts to complete the sequences. The process then imposed itself from the second week of filming. It feels like we’re following two tunnels that evolve in parallel but never meet, two characters irrevocably separated by their paths in life and by the image. The camera language was a bit complex, and, as usual, I hadn’t made storyboards. It requires a good spatial logic and I was constantly solving a mental Rubik’s cube. Once again, I slept very badly at night.

And your actors?

My three actors were the most beautiful RollsRoyces of improvisation that I could have dreamt of. But by working with Françoise and Dario, given my admiration for them, I put myself under a lot of pressure, joyful and constructive as it was. I didn’t want to screw up, to do a lazy directing job in front of a master of the image like Dario Argento, nor dare to miss a single performance by anyone with Françoise in the film. I’ve idolized Françoise since discovering her in The Mother and the Whore, even though Jean Eustache’s use of ultra-precisely written dialogues is the exact opposite of what I try to do. When Dario agreed to act in the film, I had less than a fortnight to find his son. I thumbtacked photos of Françoise and Dario on a wall and asked myself who could be physically credible as their child. Then I thought of Alex Lutz. I’d seen Guy by chance and was blown away by his performance. I stuck his photo next to his parents’ and it worked perfectly. We met, and he was available. And when he told me he had himself directed Guy from a 10-page screenplay, I figured we were well suited!

With this more ‘grown-up’ film, you may even risk getting good reviews.

Most great films are massacred when they’re released, and the worst ones are venerated…So I don’t care. To paraphrase Pasolini, what we do is more important than what we say. Vortex might be more ‘adult’ than my other films. But, I Stand Alone and my short SIDA aside, I feel as if I’ve only really made films about teenagers for teenagers. Today, at 57, perhaps I’m finally entering adulthood a little. I am getting into an unkown world.

Thank you.

Photograph: Loic Venance/AFP/Getty Images