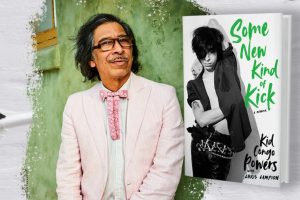

“They should build Kid Congo Powers his own personal hall of fame. Some New Kind of Kick is an instant classic of sex, drugs, and punk rock by one of underground music’s most legendary kings of cool.” – Mark Lanegan

Life is short

Filled with stuff

Don’t know what for

I ain’t had enough

I want some new kind of kick

—LUX INTERIOR

Kid Congo Powers is one of a kind. Kid Congo Powers is a real musician who has come through the shittest of times, dealt with many a shitty circumstance, and been in a few of the best and most influential rock and roll bands the world has ever seen. People of true musical nature will know of The Gun Club, The Cramps and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, all of which Kid made his name with before venturing on his own as frontman for The Pink Monkey Birds among others.

‘Some New Kind of Kick’ is his memoir, recently released for public consumption (available at all good bookstores). It’s an autobiography that has taken years to write and shows the guts this man has. It’s also a frank account of Kid’s time growing up, his denial of grief and his own sexuality, as well as being a brilliant document of his experiences with said brilliant bands. It’s also utterly amazing to read.

As well as a new memoir, Kid continues on with his band the Pink Monkey Birds and has appeared on In the Red Records since 2009. Kid Congo Powers will be feted with two albums to be released digitally by the label on October 14th: Summer Forever and Ever, the second album by Wolfmanhattan Project, his supergroup trio with Mick Collins and Bob Bert, and Kid Congo Powers and The Near Death Experience Live in St. Kilda, featuring the singer-guitarist in concert in Australia. The collections will be issued on LP and CD in 2023.

Felten Ink caught up with Kid Congo to discuss his new book, being a minority within the emerging 70s punk scene, the drugs, the loss, the exciting danger he’s sought in life, and why now was the time to disclose it all.

‘Some New Kind of Kick’, your memoir, is out now. When I was preparing for this, I looked at a video on you online when you were given the first copy of the book. You looked like a child at Christmas, so enthusiastic. You open the book, holding it, and then leaf through it. It was really sweet because you’re also holding the book almost like a newborn baby, in a way.

Well, I’m super thrilled. It’s been a very long, long process of making it, from the first time I scribbled down something and thought, “Oh, I’m going to write a book”. It’s been a long time coming and many times I thought it would never happen. Many times I just wanted to throw it into the garbage, [thinking] “Who wants to read this crap?” I’ve made lots of records, but I never thought I’d make a book. And after so much time, the whole process of editing and ‘blah, blah, blah’, going through [the process of] getting a publisher, all of this stuff, so much stuff, and it’s like, “oh, what I wanted was this book thing” and finally have something I could hold in my hands and say, “it’s here!”.

I read an interview with you from back in 2009 that references the memoir. It’s now out in 2022. What took so long? Did the process being what it is have this effect or did just being a full-time musician hold it back?

You know what? It was in all the above. Most of the time, I wrote in such small increments. I mean, in the beginning, I started writing something that I thought might be the ‘beginnings’ of a book. I had an outline. A friend that had done this was putting out a record of mine and put out this incredibly detailed timeline of my work. He was saying to me, “People know you were in The Cramps. People know you were in the Gun Club. People know you’re in the Bad Seeds. But there’s actually a lot of people who don’t know you did all of those things.” And so he put a timeline together and did a comprehensive interview. And I thought, “oh, this is an outline for a book. It would be super easy. I’ll just fill in the blanks and we’ll be done with it.” And that’s as it went.

Tell me about the preparation to help the process… did you keep diaries to look back on?

No. I went to writers’ workshops and memoir writing workshops, mostly to learn to write better, but also to see what I had. Because that’s all peer-reviewed with the people in the workshop, and in the classes. But I said, “These people have no idea who I am. They don’t know anything about the music I’m doing. Is there a story there?”. I wasn’t sure. I put a pretty juicy bit forward to them and they saw a story. I was encouraged to go on. So that takes that kind of process of time. And then also, every time it [the writing] got quite uncomfortable, I would go and literally jump out of my chair and say, “I have to make a record and go on tour for a year!”. It’s very good for my music productivity [laughs]. I used a lot of lyrics. I got a lot of lyrics from what I was writing at the time and reconfigured them. That took a long time. There were parts where I put the book down because I lost faith in it and had all kinds of self-imposed drama, a self-made drama that was completely unnecessary.

Until reading the book, I didn’t know you dabbled in music journalism.

Up to the point before I changed careers, my writing was like ‘fanzine writing’, so it wasn’t like ‘heavy duty’ journalism. It was whatever I wanted to write in any kind of form with no rules at all. But I was a big reader and also a big fan. I mean, magazines informed everything for me as a teenager, and I followed writers and I would write for my high school newspaper. I was the music critic, of course, and telling suburban kids all about Roxy Music and The Ramones. I wasn’t really formally a writer. It was just a desire. And a lot of the time for me, it was a way to be involved in music, and that was all that was important. I said, “I’m going to be in music, and I guess journalism is some form of that”. And it comes with free records and free concerts. Those are the incentives. I had a little Ramones fan club, and that was completely altruistic in the way that I wanted all the fans to know what was going on.

I wanted all the world to know about The Ramones, and I wanted them to be huge. And so I had my little following. And that was very great because I realised right away that created a community. I made friends, people were in touch with each other, and it was a very big turn-on, a very infectious thing to do. And so it was the communication between people that I saw, and I was like, “oh, I’m helping facilitate this communication”. But when I picked up a guitar, I forgot all about it.

Yes. When you realized that you wouldn’t fail as a musician, you give up the idea of being a journalist. It’s the case for a lot of us.

[Laughs] Yes, exactly.

You chose to work with a co-writer – Chris Campion. How did you go about choosing someone to deal with your material? A lot of it’s quite sensitive, personal stuff. How did you go about getting someone you could trust to accurately help you deliver what you were trying to do?

I guess I had met Chris very early on. He was a journalist and a friend of friends, so I knew him as a person first. And kind of early on, I asked him if he would help me, if I could have someone to bounce ideas off of. He was very good with that and very generous with this time because it was before there was any kind of manuscript or anything. So I worked with him a lot, him giving me pointers here and there. And as I finished a draft, the first draft, there were a couple of people interested in it in terms of publishing, It was actually my record company ‘In The Red’ that was first interested – and they don’t put out books. But Chris said, “maybe this will be a good thing to do.” And so I said, yes, but I wanted to choose my editor. So that’s when we started working, in the last five years or so, that became more of an editor relationship. And as he started working more on it, he was like, “this is good, but you’re not telling the whole thing here. There’s so much more here than what you’re saying. These are great, but you’re holding back.”

He brought stuff out of me. He had to pull it out of me. He was invaluable in helping me pull my story together and actually make a bunch of little stories into one story.

I don’t want to sound like a shrink – and you don’t seem like a shy man. Presumably, you were holding back on the tougher things you speak about in the book involving death or addiction. (Your cousin was killed when you were young and drugs became a part of your life afterwards but you’re now 25 years sober so congratulations!)

I think things were painful, mostly surrounding death. There’s the death of my cousin. The death of Jeffrey Lee Pierce. I wanted to tell a real story of really what was going on with me. And Chris said, “you have to talk about what you felt like and you have to talk about all of these things”. I am a very polite man and I didn’t want to hurt people’s feelings, that kind of thing. Chris was like, “fuck that.” Sometimes the stories at that time were a little obscured and a little vague. For a real story, in a real book, it has to actually be very clear for the reader to be engaged. And for me to really tell my story, I have to really tell my story!

I wonder if there’s a different sense of accomplishment and what you were doing in writing a memoir as opposed to making a record?

It’s a different accomplishment altogether. Making records is sometimes almost instant. I work in a very primitive sort of way, but I work in a very quick way with making records. A lot of live band stuff and then do overdubs and mixing etc, it’s a pretty quick process. This was something that I labored over with the book, I went through many drafts; I went through a couple of publishers. There was a big amount of outside things that go on with making a book and choosing photographs, contacting every photographer, all kinds of things. There are all kinds of pieces that you don’t have to deal with, with a record. The person that I’m writing about in the book does not take anyone’s advice or many people’s.

Do you look back at yourself as a younger man and think, “some things I got up to, what the hell was I doing?” – I mean in terms of sexual experiences and other things you got up to.

I don’t think that at all. I was just off and running when I was young. We were going 100 million miles an hour and not looking back. There was no reflection going on. It was just, ‘do this’. I called the book ‘Some New Kind of Kick’ for a reason, because I just wanted to get kicks when I was young. And that was great in a lot of ways and hilarious. It made me adventurous to not say ‘no’ to things like Jeffrey Lee Pierce asking me to play guitar or anything like that. The Cramps asking me to cut off a finger, etc. I realized at the age in my later twenties at the end of the book that I had been really rolling on a set of rules that I made up when I was 14 or 15 years old, and that was no longer a good set of rules for me as becoming an adult. That was kind of the lesson learned, as they say. But yeah, I hung onto it for a long time and it served me very well and I had a lot of adventure and that’s why I wrote, like a lot of stories that were misadventure, but those were the entertaining ones to me because actually, every day of my life was another one with me and my friends, a lot to pack in. It was a difficult choice. There were a lot of difficult choices.

Did you ever come to a point in your life where you thought, “Okay, now I need to get stuff down and write a memoir”? Did you just have a point where you thought, you know what, ‘I’d like to just document this stuff for my own, maybe sanity’..?

Yeah, I did. As I said I hadn’t kept diaries. I kept friends with memories, and different people. Actually, a friend of mine, Pleasant Gehman, who features in my youth in the book, she’s written a book called ‘Rock and Roll Witch; Memoir of Sex, Medic, Drugs, and Rock and roll’. I interviewed a lot of people. I called people and asked, “am I remembering this right or not?” Some things I thought, “My memory of this is really vivid.” I don’t know if it’s right or wrong but I’m going to write it because this is the way or how I remember it. I wanted to really capture the feeling of times of youth, of going through adulthood and then later of addiction and what that was like. And how dealing with success and how frightening it was. It’s actually a frightening thing. And also my constant imposter syndrome [laughs].

Why do you say imposter syndrome? I mean, being in the Bad Seeds. It seems to me, in that band there is no room for imposter syndrome at all. Every one of those guys seems like they know that they know what they’re doing and have such confidence.

You have to be an expert imposter. This is the thing. The fact was I was asked to be there [Bad Seeds] and somehow stayed there for some years and made albums. But the imposter syndrome was just something of my own making that’s in my head, it’s not reality. And so that’s what I’m writing about. Like what was the feeling behind what was going on with me and that fed into a much bigger picture and maybe a problem. We will have to get on the psychiatrist’s couch here and go deep into it. Actually, I hope it’s illustrated in the book; that a lot of all of that came from the death of my cousin when I was a teenager and being involved in gun violence as a family member and then having no adult explanation of what happened and no, nothing. It was suddenly swept under the rug except to say oh, this awful thing happened. But not really any further, no counseling and that’s when I kind of retreated into myself and then decided to take matters into my own head because life is not really worth very much, is it? But I also am going to fucking boil the hell out of life and get everything I can get out of it and experience every experience that comes my way.

It’s really good the way that you speak about your family and mother and father in the book. They come across really well. Especially, you write about your mother who you say would drink and begin opening up. Family is important and mothers are important for us lads.

Well, it’s true in a way that, you know, my mom would have a few drinks and loosen up and like I said, all kinds of things. I learned all kinds of things from her. But when she wasn’t drinking, which was most of the time, she was a very Catholic lady and very homely, a mother homemaker. And actually, our family was not really wide open with family secrets or just about anything, really. There was a lot of love and there was a lot of care. But on a deeper level, I think maybe I’m holding on to things. We’re back in the psychiatrist couch because of the death of my cousin and how that was handled by my family and I don’t blame them. This is just the way it was. It was very much a ‘clan Mexican American family’. Everything stayed in the family. Don’t tell outside. It goes to anyone outside what goes on in the family. I grew up with that kind of thing and obviously, being a rebellious teenager, I wanted to kind of go the opposite way and blow up everything. Blow it up! [laughs]

I’m referring to any kind of structure I had in mind for this and while I can’t believe how long we’ve been going, I also think we’ve gone off track.

It happens. You have to reel me in [laughs]

I think you’ll have to reel me in as my mind is wandering. On reeling you in, this reminded me of a few months ago I interviewed Blixa Bargeld, whom you obviously worked with in your time with the Bad Seeds. Like you, he is a real character. Although Blixa was very ‘Stone Cold Jackson’ and there was no problem for a lack of ‘reeling anyone in’.

[Laughs] I already knew him socially before I joined [The Bad Seeds]. And also I had met Blixa in Los Angeles. With Blixa, I gave him some socks because his tour manager, Jesse, was like, “oh, my God, his feet smell, like, so bad. He wears those rubber boots every day. That’s in the tour in the van, it’s awful.” And she was like, “Don’t you have any socks to give him?” My mother had for Christmas given me a big package of white socks. And I’m not going to wear white socks. So I said, “Oh, here, hey, nice to meet you, Blixa, here are some socks.”

So he was very happy with that. And Jesse was overjoyed, and I actually loaned him my guitar because he was doing a concert out in the desert. It was nice to see him bury my guitar in the sand. He was very polite. I already had a pretty funny relationship with such a serious artist. He’s an amazing artist, intense, but it’s what you would expect.

I’m also a huge fan of The Cramps and your time with them is also fascinating – where you talk about how you were obsessed before you joined, and Lux/ Poison Ivy perhaps played on that. With that in mind, what was your level of influence like with them being a young man and a ‘fan’?

Yeah, I think there were ideas that I flew there, but I don’t know if ‘influence’ was a thing. I think they were the visionaries. It was strictly their vision. I was just helping to decorate the cake. I’d like to think there was some influence, but you would have to ask them. But, yeah, I came with a definitely different approach. I was super self-taught, open-tuning, just different things. It was strictly their vision. And I knew that I was young, I’d been playing guitar for one year, I was going to do whatever they asked me to do and I was learning, learning on the job sort of thing. They were very generous in wanting to teach and indoctrinate a young person with no experience. The Cramps had actually taped one of our shows [with Gun Club]. Lux taped our show and actually, that tape came into my hands just recently through various channels.

And it was with the Cramps you got your name Kid Congo Powers (originally Brian Tristan). You must have liked it since you stuck with it?

I like it, yeah. Sometimes I think, oh, Congo is unfortunate, it has some not-so-good connotations. It came in a way, a pretty humorous way. We were trying to think of a name because if you’re in The Cramps, you have to have a ‘Cramp’s name’. And Lux Interior just looked at this voodoo candle and it was called the Congo Candle and he said, “When you light this candle, Congo Powers will be revealed to you.” And he said, “That’s your name, Congo Powers.” So that’s stuck. No, it sounds good. I’m like Iggy Pop. He doesn’t change his name to James. It’s good. Madonna has not changed her name.

It’s really good because you could always go up to a club or a concert and say, “I’m on the list, Kid, Congo Powers.” And they always go like, “I don’t see his name, but you must be someone with that name.” And I think that’s the kind of thing The Cramps really were about, like creating an out-of-this-world sensation. So the name had to fit that and have that effect.

You have a great sense of humor which comes across in ‘Some New Kind of Kick’. I was reading through the book and found the section on ‘Mr. Big in the Pants’, which was funny to read at first. This was the tale in which you talk about giving your first blow-job. For reference, it goes somewhat like this:

“I walked on to Hollywood Boulevard, by the Gold Cup, and headed down to Highland Avenue, to a secondhand record store called Railroad Records. Just as I got to the Arby’s drive-thru nearby, a guy sidled up to me as if he wanted to talk to me. I was a bit taken aback, but he looked friendly enough. Up to that point, I had felt quite anonymous, despite walking around in glitter platforms. Now, this hip-looking cat wanted my attention… but the apprehension at what was expected of me now was not enough to deter me from throwing caution to the wind and furthering my dalliance with “Mr. Big in the Pants.”

On re-reading that, I began thinking about Jeffrey Dahmer [at the time of writing Netflix has many shows on the serial killer] and how that situation could have….

….have gone that way, or the wrong way. Yeah. Totally.

Yes. But it’s the danger that makes a situation more interesting?

Yeah, I think I make it clear in the book. I make a point of it, but it’s clear that it was the danger that was interesting, the enjoyment of fear. So that was part of it. Now I think about it and go, like I was probably in some bad situations that I didn’t even know, like that one for sure. I mean, I could have become just said, okay, I want to be a street hustler too. That sounds great. That probably would have been no kind of life.

About the ‘blank generation’ you talk about in the book. You say you and those you were around didn’t want to be part of any movement, in the sense of the ‘Gay’ movement…

It’s a fact now. And speaking up for yourself and your, basic civil rights, is always a good thing. But I mean, I’m talking when I was involved in subculture punk. Punk in Los Angeles was a very small subculture at the time I’m writing about. And it was also yeah, we were going to be separatists and the rules were like, you’re a punk and that’s what you are. And under that umbrella, there were a lot of queer people, trans people, just any kind of person who could say they were disenfranchised, Latino, Black, everyone. It was kind of all, except that all you had to be doing was bucking the system. And so being Latino, being a Chicano queer person was 100% bucking the system. But I don’t know, John Savage wrote the introduction and he makes a good case. He frames it as my being a queer man in punk. He points out there was a readymade community out there to help. The gay punks rejected it, obviously being anti-authority, and mainstream gay culture was authority, or we definitely saw it that way at the time.

On that I have the impression that ‘punk’ may be at times, maybe even more so when you were involved, be quite volatile. Did you ever get any problems being part of that sometimes ‘macho’ world for being openly gay?

Oh yeah, from like dickheads? Like, you know, whatever. Yeah, I don’t know if I did. I didn’t suffer gay bashing, so that’s thankful. But other than muttered whispers, I don’t think there was really any much consequence. And I was in a group of people who were queer people. Everyone knew who everyone was and who everyone was sleeping with. It wasn’t like a negation of being gay. The representation was not there, and it wasn’t for me. It wasn’t until the AIDS epidemic in the early 80s that it became apparent that you had to be out and you had to be outspoken and you had to become politicised. Up to then, I hadn’t even thought about it being politicised. It was just a subculture to me.

The book ends in 2007. Why then, was that to do with drugs, in the sense that it was when you became sober and around the time when Jeffrey Lee Pierce died?

Yeah, I think so. It’s to do with getting off drugs. I think it was the end. It was that I got into recovery and finally, for the last time. It was the same time, Jeffrey Lee Pierce died, like right after. And that, to me, is an end of an era. With this book, I credit him with my whole music career and everything. It wouldn’t have happened without him. And like, when I say, like, The Cramps, the music was their vision. The Bad Seeds’ music was Nick’s vision. The Gun Club actually started out with art, my and Jeffrey’s vision for music, and what kind of music we wanted to make. And so through the years, I was in and out, in and out, and I was in at the end, I was out. But we were talking weeks before he died, we were talking about doing something else again. So I just felt like that was the end of an era and that I was going to have to, for real, go solo and do my own things. I didn’t have Jeffrey to consult or confer, conspire with or compete with, or whatever we were doing.

He was a kind of standard-bearer of quality for me. And also our relationship had gone through so many ups and downs, through so much, and I didn’t feel like he was ready to go yet. He was writing that book for Henry Rollins’ Press. Henry commissioned a book for him. That’s what he was doing when he died. He was drying out at his father’s in Salt Lake City. He was clean again, and he was happy, but he had been quite a mess. And I kind of go into that in the book. It’s funny because I talked to Mark Lanegan, because he wrote nicely about Jeffrey in his book and talked about what an influence he was and how much he loved Jeffrey as a person because they matched. We had the same story that people kept saying, “oh, Jeffrey is just a mess and the worst, and it’s the end, and you better..” whatever. And both of us had we coughed him up, (what does this mean?) he was just like, hey, what’s going on? And he was just Jeffrey. And Mark had a poignant quote that he said when you talk to him, he said, everyone says you’re about to die.

And then Jeffrey said, everyone always says that. Everyone’s always said that. It did finally happen, but unfortunately but it was the end of a creative friendship, a brotherhood. And so I thought that was good because it really, to me, defined the end of an era in my life where I had to once again just make up, become myself. I didn’t have that codependency of being with Jeffrey at all times and just it was a constant that was always there and kind of grounding for me. Imagine your grounding is every purse. But he was an amazing, creative person and a great friend to me.

I’ve been through it a lot, actually. It’s over 25 years ago. Yeah, but still we have done some healing. I can talk about it. It’s fine. It’s in my book. I wouldn’t have written about it if I didn’t want to talk about it. I think grief is good to talk about.

Kid Congo Powers, thank you so much.

Kid Congo’s new memoir, ‘Some New Kind of Kick’ is now available to buy through Hachette Books

And ‘Some New Kind of Kick’ is also available on Amazon.