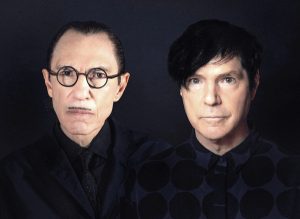

Annette is a Leos Carax-directed musical, written and composed by the legendary Sparks brothers, involving a Bill Hicks-like comedian’s love affair with an acclaimed and much-loved opera singer. And it also has a baby puppet at its arc… Still with me? John Waters recently described this as his movie of the year, affirming that you need to see it for yourself so that ‘no one you know can possibly ruin this nutcase masterpiece’. These terms go hand in glove when it comes to talking about either Leo Carax (Holy Motors admirers will abide) or the music of Ron and Russell Mael. Both Carax and the Sparks were awarded for Annette at this years’ Cannes Film Festival, with Carax winning Best Director in what was an extremely competitive year (Please watch Titane after this). In a lengthy Q+A with the writer-director, Carax went into great detail about the making of his English language debut feature, what it was like to collaborate and work with the likes of Sparks, Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard (as well as the importance of a baby puppet), and the relationship between one’s artistry and decency. There was also room for discussion on pet monkeys.

When did you first encounter the music of Sparks?

When I was 13 or 14, a few years after I discovered Bowie. The first album of theirs I got (stole, actually) was ‘Propaganda.’ And then, ‘Indiscreet.’ Those are still two of my favorite pop albums today. But later, for years, I wasn’t really aware of what Sparks was doing, because by the age of 16, I started to focus on cinema.

And when and how did you meet Ron and Russell Mael and tell me about how you all became involved in ‘Annette’?

A year or two after my previous film, Holy Motors, came out. There’s a scene in which Denis Lavant plays a song from ‘Indiscreet’ in his car: ‘How Are You Getting Home?’ So they knew I liked their work, and contacted me about a musical project. A fantasy about Ingmar Bergman, trapped in Hollywood and unable to escape the city. But that wasn’t for me: I could never do something that is set in the past, and I wouldn’t make a film with a character called Ingmar Bergman. A few months later they sent me about 20 demos and the idea for Annette.

What has been your relationship to musical films? Is the idea of

making a musical something you’ve been thinking about for a long time?

Ever since I began making films. I had imagined my third film, Lovers on the Bridge, as a musical. The big problem, my big regret, is that I can’t compose music myself. And how do you choose, work with, a composer? That worried me. I didn’t watch many musicals when I was young. I remember seeing Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise, around the same time I discovered Sparks. I eventually saw American, Russian, and Indian musicals later. And of course, Jacques Demy’s films. Musicals give cinema another dimension —almost literally: you have time, space, and music. And they bring an amazing freedom. You can direct a scene by following the music’s lead, or by going against the music. You can mix all sorts of contradictory emotions, in a way that is impossible in films where people don’t sing or dance. You can be grotesque and profound at the same time. And silence, silence becomes something new: not just silence in contrast with spoken words and the sounds of the world, but a deeper one.

Was Annette always meant to take on a sort of rock opera musical form?

There was always the operatic, some rock but not much, and Sparks’ unique mix. I have always been struck by how you take formal and experimental risks, but you’re also not afraid to make visual gags with these very physical actors. Annette is about two performers.

How did you conceive of how to show their performance domains?

I first wondered: why is she an opera singer, why is he a stand-up comedian? Sparks’ world is pop fantasy, with multilayered irony. But I had to take it all seriously at first. And I knew nothing about opera, and just a little about stand-up comedy. I quickly became very interested. These two forms, so far apart, do share a few things. The nakedness, vulnerability, of opera singers and comedians on stage. The game with death: opera is basically women dying on stage, in every possible way, while singing their most beautiful, poignant song, called the aria; and great comedians, like Andy Kaufman, are the ones who flirt with death on stage. Grotesque is essential to comedy, while serious opera avoids it, but is often mocked as grotesque anyway. And singing and laughing are both very organic: they rely on a complex anatomic system, the same vital system for how we breathe. I started to see the whole film as a metaphor for breathing: life and death of course, and laughing, singing, giving birth, holding your breath, … Also, breathing as a musical rhythm. In the prologue, we can hear your voice asking the audience to stay focused and to hold their breath!

Which now takes on a new meaning, since Annette came out during COVID, when

you’re not supposed to breathe too much in the company of others. Life and death, again.

Backstage musicals, like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, the films of Vincente Minelli

and Busby Berkeley, sometimes make profound comments about the essence of

performance and connecting to the audience. Was that on your mind when you were

making Annette?

When Sparks gave me their first songs and a treatment, I had one big concern: the guy was a stand-up comedian, but there was no sense of what his act was like. I had seen some stand-up in France, as a kid and later. And through my parents, I’ve always loved Tom Lehrer. He was a math teacher who started doing stand-up in the 1950s, singing and playing piano. His songs are very tongue in cheek — a little like Sparks’ actually. In my first film, I had stolen this line from him: “It is a sobering thought that when Mozart was my age, he had been dead for two years.” And I used a bit of one of his songs in Annette — bu this time with his permission.

I also knew Lenny Bruce’s and Andy Kaufman’s work. I started reading biographies about them and others —Richard Pryor, Steve Martin, … Some comedians vomit out of panic before their act. To enter the stage knowing that you have to make people laugh… Must be terrifying. Like if I were forced to go on stage at Cannes… and to go naked. So there was a dual theme: opera, the woman who dies on stage, with music and grace; and stand-up, which involves grotesque —and provocation, to the point where it can become self-destructive, as you can see if you watch any great comedian perform. The story of Annette is so archetypal and contemporary at the same time.

Do you remember your first emotional response to the story when Sparks presented it to you?

I loved the songs right away. I felt fortunate, and grateful. But at first I told them I couldn’t do the film. I had personal worries. I have a young daughter —she was 9 at the time. And although the brothers knew nothing of my life (I think), there were some things in the

storyline that could upset her. And did I really want to —could I— make a film about such a “bad father,” at this time in my life? But as I was listening to the songs over and over again, she started to love them too and asked me what they were. I told her and realized she already understood a lot; and that by the time the film would get made (if it ever did), she would understand how a film project comes to life. So I said “Yes.”

At the time, did you have to find strategies to make the film your own, so you could make

it?

Music is so intimate. I couldn’t see myself doing a musical if I didn’t feel for every note in every song. I was worried about that, especially since we were trying to have the whole film in songs. Musicals usually have 10 or 20 songs — with often half of them boring. But we had to create 40 songs: 40 songs I could see, then film. And how do you work with music when you’re not yourself a musician? But the process with Sparks was miraculously simple: they’re very inventive and humble and fast, with that unique sense of melody and rhythm, melancholy and joy. And I’d known their music for so long; it felt like going back to my childhood house decades later — but a house with no ghosts. There’s a risk, when you have so many songs, however great they are, that the film will become a cloying cake. Or a jukebox playing too loud too long. Which would have killed the experience. So you have to be very careful with the total score, the same way you have to be with the totality of your film when you edit a sequence. It’s a matter of finding the film’s natural breath. Another concern was: how to create Henry? A Henry I could relate to. And what true father-daughter relationship could I imagine, in this context of “exploitation?”

Can you talk a bit about the opening sequence, with the ‘So May We Start’ song? Is it

meant to be an introduction to the film?

Not really to the film, more to the film’s specific form. It owes a lot to Sondheim’s great ‘Invocation And Instructions To The Audience.’ And also, to the tradition of the opera prologue, especially the beautiful one from Bartok’s ‘Bluebeard’s Castle.’ As with the first scene of Holy Motors, you’re in it. Yes, and again with my daughter. I had imagined it for me, her, and our dogs (but we couldn’t bring the dogs to LA.) For Holy Motors, it was important to be there with her at the very beginning of the film. Probably to reassure myself, after all these years of not making films, that we were just doing a small experimental home movie. In my mind, these last two films are experimental films. Annette is a big one; Holy Motors was a small one. I think of them as “films I have made since becoming a father.” It’s interesting to compare both films: Holy Motors was so experimental, and you’re right Annette is as well, but it has much more of a traditional story arc. Much more than any of my other films I would say. That comes from Sparks. They came with this dark fairytale, which I think respected.

And with Holy Motors, Kylie Minogue of course brings things towards a ‘musical’

Toward the end of Holy Motors, Kylie Minogue sings a song that mentions having a child… Losing a child, actually. It was the first time I wrote lyrics for a film. Neil Hannon, from The Divine Comedy, wrote the song’s music. A very good experience, and a step closer to making a musical. I had always worried about what would happen if I asked someone to write music, and then didn’t like it. But we got to a song I liked a lot, and filming Kylie was beautiful. So it gave me confidence.

Did you have the desire to make a film in America (or in the English language) before this?

To make a film in English, for sure. English was my native language. But no, shooting in America was never a strong desire. About 20 years ago, I had a project called Scars, a tale set in Russia and America —New York, and on the road to the West Coast. And in the 1990s, an adaptation of Peter Ibbetson, set in France and America. In those years, after Lovers on the Bridge, it was impossible for me to make films in France. So I considered making films in the US. It seemed possible, or less impossible. Annette also started as an American project, with producers in L.A. I kept getting emails from them, with the word “hyperexcited” written all over them — but nothing was really happening. So I brought the project back to Europe.

Can you talk about shooting in L.A?

The film was imagined for L.A. The Mael brothers live there, were born there. In all these years of pre-production, I was asked again and again to move the film out of L.A, because shooting there is so expensive. I tried to imagine other cities but they didn’t work as well. I wanted Henry to travel on his motorbike like a cowboy, between his world and Ann’s world, and that wouldn’t have worked in New York, Paris or Toronto. So we had to reinvent LA, mostly in Belgium and Germany (which are not very Californian countries.) A fantasy version of a fantasy city. We only shot in LA for a week: the prologue, the motorbike shots, the forest amid the canyons and hills.

Annette is a return to the boy-meets-girl theme of your past films. There are shades of Alex

[Denis Lavant’s characters in the first three features] and Pierre [Guillaume Depardieu in

Pola X] in Henry. They meet someone that they have this intense spiritual attraction to,

but because they can’t live up to their own high expectations of either the relationship

or themselves, they submit to this death drive of destroying themselves and the

relationship. Do you see a connection between those male characters?

I see a connection between the actors: Denis, Guillaume, Adam. First of all, they’re interesting people, and not all actors are. I had only seen Adam in the TV series Girls, and I thought, like Prince Myshkin when he sees Nastasya Filippovna for the first time: “What an extraordinary face.” And also, an extraordinary body. He reminded me a little of Denis, although Denis is short —my size— and has a face people call strange. Adam is tall, with a beautiful face that some people would also call strange. Guillaume and Adam share a similar physicality: they’re strong, feline, very handsome young men, with something both feminine and masculine.

In Henry’s performances, he talks a lot about laughter, but it’s not a joyful laughter that’s in the film. He uses very personal aspects of his life as fodder to make people laugh, and then later on he uses laughter as a menacing weapon against his wife. Laughter becomes a question of life and death. We needed to invent two very different shows that would fit into the narrative. That was a big challenge, hard work. I forgot how many versions we tried, all very different. And since at first we wanted everything to be sung, it meant writing the entire shows into lyrics —and it had to be funny in a way no other comedian has ever been funny. I couldn’t find a way to do that. Then one day I thought: maybe Henry doesn’t always have to sing; he could go from singing to talking to mime. I felt liberated. I was consulting an American friend, Lauren Sedovsky, on the project. She knows a lot, about everything: art, literature, philosophy, … She told me about this old mime play by Paul Margueritte, called ‘Pierrot assassin de sa femme’, in which Pierrot searches for the best way to kill his wife, and finally decides to tickle her to death. It was the perfect inspiration for our laughter, breath and death theme.

Did Adam Driver have any input into Henry’s monologues on stage?

Not in terms of writing but in terms of acting, very much so. I usually don’t rehearse, ever, I hate it. But I did rehearse the two shows with him, each one for a day, at the beginning of the shoot. To reassure Adam. And myself, too. We knew each other so little. I also needed to check the rhythm of these two long sequences, and how Henry should move on stage. How he would play with his mike, etc. And Adam proposed many things. So the shows were really a collaborative creation between Sparks, Adam and I.

Tell me how you came to work with Marion Cotillard?

I first met with American actresses (Ann was supposed to be an American). But I couldn’t find Ann. Then I thought of singers who could maybe act, but still couldn’t find her. I was getting worried: apart from money and reputation, the other main reason I have made so few films is what people call “casting”. I see casting as a totally unnatural and absurd practice. And each time I had imagined a project without an actor and actress in mind, I had to abandon it — could never find the right actors. So I felt doomed. What would happen if I never found Ann? Could I, for the first time, force myself to work with an actress I didn’t really want to film? A few years before we finally shot Annette, I met with Marion. Without much hope since, for some reason, I thought we wouldn’t get along. So I was surprised to actually like her very much, and believe in her for Ann. But there was, of course, a problem: Marion was pregnant so couldn’t shoot when we were supposed to. But the film kept getting delayed anyway because, as always, financing and production were a mess: I had to change producers three times, etc. So two years later, I offered the part to Marion again, and Adam and I were very glad when she said “Yes.”

You said that you don’t like rehearsing with your actors. I was wondering if you do any of

the traditional things when you direct them? How do you know when it’s right?

These questions are always hard for me to answer. Cinema is something I’ve done so sporadically, just a few films in 40 years, and when I’m not in the action, I tend to completely forget how it’s done, or how I do it. I can’t see myself doing it. But I think it always involves an obscure mix of extreme precision and extreme chaos. Directing has a lot to do with choreography, all the more so for a film like Annette. Although it’s a musical without any dancing, the music and singing force everything to move differently. And if you do it right, bodies, cars, trees appear to be dancing. Working with actors is, again, all about precision and chaos. Marion is at ease with both, but more on the precision side. Adam, at different times, needs one more than the other. So for some scenes, he would feel lost, get mad. I was asking for too much precision, or leaving him in too deep a chaos. Those scenes are of course the ones in which he delivers his most inventive and inspired work. Maybe we’re a bit the same in this way. I loved filming Adam. I shoot many takes. Less now than I used to — since I’ve turned to digital, I don’t watch dailies anymore, so I don’t feel the need to retake every shot like I used to. Sometimes, you want another take because you’re looking for something specific. But more often, it’s the opposite: you need to get lost, to reach a point that is, to me, like a déjà vu illusion: where it seems like you’re in the middle of a dream… or that you have seen or dreamt this before… “I’ve been here before,” but I never knew it.

In Annette, the songs replace regular, naturalistic dialogue. You get used to characters

singing to each other. How did you decide for the songs to take on a very casual

conversational quality and how did you communicate that to the actors?

The first decision was to have the actors sing live. An evident choice for me, but not easy for the people involved —sound people, camera people, money people, and the actors of course. It implies not going for the performance. Singing becomes more natural, like breathing. It’s something that’s quite moving to do, and to watch. It was easier for Adam than for Marion I think. Marion always felt her voice could be better; Adam didn’t have this concern so much. Once we started shooting, he was an actor, not a singer. I like how both of them sing in the film, each in a very personal way.

I remember you saying that a lot of films start as a single image for you. Was there one

for Annette that triggered the rest of the film?

Since it was not my original project but Sparks’, Annette really started with the music, their music. The vertigo of music. And although I didn’t write any of it obviously, I often felt more like a composer than a filmmaker. Which I guess has sometimes been the case on my other projects anyway. I didn’t have any actors in mind, and especially had no idea how to show a baby, from age zero to six… a baby who could sing… The film seemed impossible to make. But I’m used to that, and every film should be impossible to make. The first image that came to me was more of a feeling or an intuition: a tiny star, alone and lost in the dark infinite — the smallness of Annette in the face of the world. And then I thought of Masha, a little Ukrainian girl. Years ago, I had lived with her young mother and her, in Ukraine. She was two years old then, and a wonderful child. At times, she almost looked like an old lady; but she was beautiful, in a very particular way that moved me. Masha would be the inspiration for Annette.

You once mentioned that animation wasn’t really your wheelhouse. Do you still feel that

way?

Yes. I can enjoy it for a few minutes. If my daughter really insists, I watch a Miyazaki with her for example, but I’m not interested in it. I like real movement. And my love for cinema starts with: a person looking at another person. A man filming a woman of his choice, a

woman filming a man of her choice. I like filming nature, cities, a gun, engines, fireworks and explosions, … But I need above all a face, a human body. Skin, eyes — and the emotions reflected in them. Annette herself is at first this puppet figure.

How did you come to that decision?

Like most decisions, by first saying “No, no, no” too many things. “No” to a digital baby; “No” to 3D imagery. By personal taste or distaste, and because of what they call “the uncanny valley.” Which would’ve been even uncannier in the case of a small child. And because if you do it digitally, it’s all post-production, which is anti-emotional. I couldn’t see myself shooting the film without Annette among us on the set, by herself or in the arms of the actors. Then I said “No” to using robotics or animatronics: Annette had to be someone, something I could understand, not a computer. Something simple, hand-crafted. So I thought of a puppet. I knew nothing about puppetry — but at least, hopefully, someone could create an emotional puppet.

A concept suggesting that humanoid objects which imperfectly resemble actual human

beings provoke uncanny feelings of eeriness and revulsion in observers

It’s a big risk that you took.

An exciting one. But did I have a choice? And, maybe for the first time, I had to really think of a future audience: were people going to accept a film in which a puppet suddenly appears, and nobody ever mentions she’s a puppet? A film in which none of the other characters, played by real people, ever see her as a puppet (except Henry, maybe). But the film is a musical, and I don’t make naturalistic films anyway, so the reality of the film was already out of this world. I imagined the scene in which Ann gives birth to Annette as a way to introduce the baby puppet to the audience. In the world of the film, she’s a real baby, but we can see right away that she’s not a baby of flesh and blood.

With the Showbiz News bits, does the film try to get at the notion of celebrity and how it

can be such a destructive force?

That has more to do with the roman-photo aspect of the film’s first part. The couple is “rich and famous.” I find it very difficult to film rich people. Again, this irony problem. The two films of mine that do portray rich people, Pola X and Annette, are the only ones based on

stories I didn’t imagine myself. Sadly, I am not Douglas Sirk, and the times have changed since the 50s, when the rich & famous could still be seen as substitutes for vain and vulnerable gods in a Greek tragedy. But success is very interesting —I also used the theme in Pola X. Whether one wants it or not, and then achieves it or not, and then whether success is personally successful: whether it makes you grow or shrink. I had decided that Henry would come from a poor and violent childhood, while Ann would come from a boring but safe childhood. There’s also the fact that opera is seen as high, refined, art; whereas stand-up is considered a popular or even vulgar art. So there’s almost a class war there. Of course, like in many love stories, this discrepancy is one of the reasons they fall in love in the first place — the press calls them “Beauty and the Bastard”. But then, Henry becomes like these guys who see a stripper in a club, fall in love with her, marry her, and then beat her up because she’s a stripper.

I was struck by one of the lines in Henry’s performance: “Comedy is the only way to tell

the truth without getting killed.”

Oscar Wilde said something like that. But we all have to go through this. We all have to find our way of telling the truth without getting killed. I mean the truth about ourselves.

And what about the motif of monkeys in the film?

When I was small, my father had a female chimpanzee, Zouzou. She was very jealous. He kept her in the bathroom next to the parents’ bedroom, on a long chain, and at night she would jump on the bed and attack my mother. A few years later, I had two monkeys of my own, Saï and Miri, small ones with long tails. It was a very sad, very morbid experience. They got sick, dehydrated. I put them in a small drawer in my desk with some cotton, and each time I opened the drawer I would see them trembling. We finally had to euthanize them. Monkeys represent both dangerous wildness and martyrdom. I love them.

How did monkeys get into Annette?

I think it was the result, as it often is, of a few coincidences. I was looking for a title for Henry’s show, and remembered that some ancient theologist had called Satan “Le singe de Dieu.” So I called the show, “The Ape of God,” which sounds like a wrestler’s ring name. Then the puppeteers suggested that baby Annette could have her own toy, a teddy bear, and I liked the image of a puppet puppeteering another, smaller creature. But I chose a monkey, not a bear. And then I saw that one of the young puppeteers had created, for one of her own shows, a big Kink Kong puppet, and I absolutely wanted to use it in some way in the film. So gradually, monkeys invaded the film, and became a link between father and daughter, savagery and childhood.

The scene with the six women coming forward feels like a dream sequence, removed

from the reality of the film. Ann is in the back of the car, falling asleep…

I had a hard time imagining Henry’s fall from grace. In the original treatment, he just became less successful over time. But I wanted it to be sudden. So I started imagining things that could go very wrong with one of his shows. It had happened to a few real-life comedians. Michael Richards became famous with the sitcom Seinfeld, but one night, as he was doing his stand-up show, he suddenly went into a wild racist rant, and then had to retire from stand-up. Dieudonné was a very successful French stand-up comedian, politicized on the left, who for some reason moved to the far right, and whose anti-Semitic provocations kind of killed his career. And Bill Cosby ended up being convicted and imprisoned for raping women. But these cases, involving violence, sex or racism, were too real for our film; they would make Henry too obvious a villain, too early in the film. So I thought: first, he won’t do anything terrible, he’ll fantasize about something terrible, and people will hate him for

that —because comedy’s truth does have its limits. And then Ann too should fantasize about something terrible, in relation to him. He has visions of her, dying again and again on stage, and plays with the idea of killing her. And she dreams of him being accused of having abused women.

Were you thinking of bad male behavior and how it’s connected or not connected to

artistic output in the creation of Henry’s character?

Yes, but it’s something I’ve always thought about. Bad men, bad fathers, and those male artists who were terrible people but inspired me so much. Starting, when I was young, with the great French novelist Céline, who became mostly known for his anti-Semitic lampoons during the Nazi occupation of France.

Do you think it’s too much to expect from artists to also be good people?

Not too much, but it’s not the right expectation. There are of course great artists who seem to have been beautiful human beings, like Beckett, or Bram van Velde. As far as we know, they suffered, but didn’t make others suffer. And their beauty imbues their work. But I’m not sure there are many such artists. Was Chaplin a good person? Or Patricia Highsmith, whom I like a lot? The two most gifted comedians of our time, in my mind, are Dieudonné and Louis C.K. One is a fascist lunatic, and the other apparently forced women to watch him masturbate. Annette only turns into a real girl in the end, when she’s totally alone. That’s the Pinocchio side of the film —and the reason why I added that last scene in prison.

And it’s often the truth: it’s when kids get rid of the adults that truth comes out. That’s what I experienced. And that’s why I changed my name when I was 13. I don’t want my daughter to ever push me away, but that’s how it happens. Annette appears and says to her father: “Yes, I have changed, and it’s over. Now you have no one to love.”

That’s a very shocking scene because she’s this innocent little girl, and although she’s

been through a lot, you don’t expect that she has necessarily processed all of it. And yet,

she’s so determined to break her bond with her father who is her last relative. That must

have been very difficult to write and to shoot.

Very. But films with certainties are not interesting. Films become alive when you spill your doubts and fears into them. When you confront what seems impossible, unimaginable to you. Like your daughter turning against you. I wanted to ask about this motif of the orphan, which you’ve talked about before. This sort of childhood wish fulfillment: a dream of waking up in a world where you’re all by yourself, a sort of scary but also totally freeing dream, which you have compared to the experience of being in a film theater. Annette literally becomes an orphan at the end. I feel very close to her. It’s like in The Night of the Hunter, but she has no big brother and no Lillian Gish to protect her. She’s really left all alone with that man-father. Cinema is for the orphan in us. I remember the experience, when I first came to Paris, of discovering films, alone in the dark, especially silent films. It had these same elements of freedom and dread.

I heard you were alone when you were quite young.

Fassbinder once said “I was left alone to grow like a flower,” because was also raised without much oversight from his parents. I think it’s a blessing, for certain children, to be left alone when there is too much chaos around. They benefit from tragedy, family tragedies, by being left alone. The chaos allows them to invent or reinvent themselves.