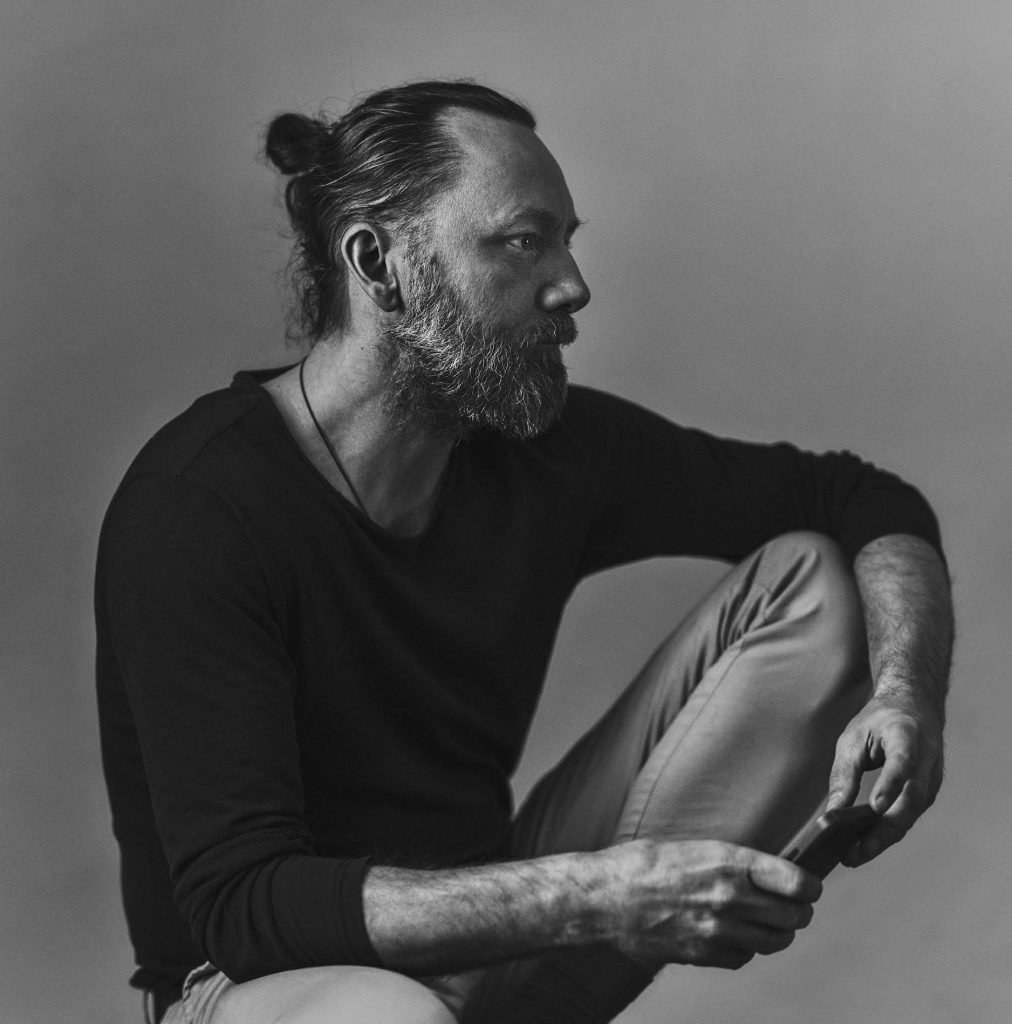

Michal Korta is an award-winning photographer widely known for his ability to capture captivating and unique portraits but also haunted images of nature in his personal projects. He has been working for just over 20 years, is well recognized and heavily exhibited in his native Poland and abroad. I would argue his work studies and almost celebrates the harsh beauty of the natural world, whilst also raising awareness about the importance of ensuring it lasts. Judge for yourself.

Over the years Korta has worked with many organizations and institutions like the National Museum in Warsaw, Krakow’s International Culture Centre, Cricoteka, Calvert Gallery and Unicef. His works have been published in magazines such as Newsweek, The Guardian, The Boston Globe, Forbes, Elephant Magazine and Vogue. In 2016 Art Verseed named him one of 5 Eastern European photographers to follow. He is also the managing director of Kowalsky Gallery – an independent space for contemporary photography.

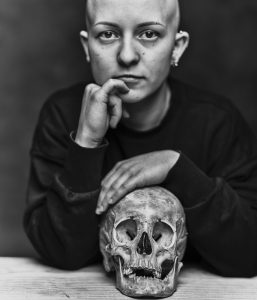

I was first taken aback when viewing his project ‘The Shadow Line’ from 2016-2020, a striking exploration into ‘the wild’ darkness which we discuss in this interview. “It all started with one skull”, he points out. He has traveled to many remote, difficult and exotic landscapes to photograph people and locations, including Europe, Africa and Central Asia.

Michal very kindly spared me his time to discuss the themes of his work, the unavoidable obstacles that get in the way, the process of choosing projects, and the trickiness of synchronicity.

Michal, I was first drawn to your work via The Shadow Line series. What first drew you in yourself and what was the process like for you?

I grew up in a small town in southern Poland and as a kid, I spent all day playing in the gardens or small forests nearby. There were always friends and dogs around, you know, [playing] the typical children Apache/Indian game. From today’s perspective, I think we were very brutal and far from mindful, but at the same time, it was full immersion in the ‘here and now’ and the surroundings. Somehow, I think this shaped my vision of the natural world. A few years ago, I also had a dog, a kind of African greyhound (Azawakh) and he was my companion on some road trips. I always walked the dog a few times a day and sometimes also late at night. It all started with the one skull I found in the ditch on some local road trip to the mountains. I took it and after some time I decided to take a “portrait” of it. I was reading a lot of essays about animals, animal behaviour, feelings, instincts, and the light compass of some creatures. I started to notice the animals around us more and more. We, as humanity seem right now almost reaching the end of supremacy as creatures. It’s the end of the Anthropocene as we’ve known it [for the] last few hundred years. The project appears to be about animals but it’s more about our perception of them. I think the night hours, even in the city or on the outskirts, is the time they ‘activate’. And also, the light separates the object better from the photographic perspective. I perceive the project as a kind of precedent. The project’s ‘ignition’ was rather an organic combination of feelings, mood, reading, and thinking.

With regards to the animals you photographed, I’ve read you say that you wanted to look them in the eyes. Do you feel you captured, so to speak, what you wanted?

I’d like to know if they have souls, feelings, and emotions – and how are they comparable to our human understanding of those feelings. We already know that some animals show anger, happiness, or fear – in the behavioral sense, but are they aware of those feelings? And if yes, how far? What is the difference between looking into the eyes of a human being and an animal? There can be no doubt of some kind of connection between a man and a dog…

The project may have been called ‘Darwin’. I would assume Charles Darwin is a figure who interests you.

While working on this project, I was reading many books about behaviorism and the evolution of species. Darwin’s theory was ground-breaking for natural science. And according to his theory, we are also part of the animal world, having common ancestors. Along the way, we’ve lost (or suspended) some of our senses. They are not used for surviving anymore, but something interesting happening to your senses when you go into the woods at night in the rain.

What was your plan before setting out to find what you wanted?

The project started rather unconsciously, like most of my projects. It’s not like I have an idea and I start to think how to show it through photography. If I’m fascinated by an idea, I think of it all the time, and it develops in me organically. It grows, every thought circles about it for months, sometimes for years. Occasionally I start taking pictures, first without any specific plan. It’s compulsory. And then after some time, I look at what I created and then I realize if it can be a project or not. Then I look at the form, I shift it if needed and so it goes… In this case, I was thinking about book publication and I decided to create those two layers. High-quality studio reproduction of skulls, perfectly lit on black background, as a kind of ornament or interlude, decorative and symbolic at the same time. It’s a kind of synthesis. The meaning of it is that we are equal to animals concerning death. The pure white bones … And the other deeper kind of content layer with suggestive, blurred, night images of spotted animals. It’s kind of the opposite of controlled studio images. It’s like emulating the animal’s language. As Tomas Tranströmer once nicely said in his poem:

“Tired of all who come with words, words but no language

I went to the snow-covered island.

The wild does not have words.

The unwritten pages spread themselves out in all directions!

I come across the marks of roe-deer’s hooves in the snow.

Language, but no words.”

Synchronicity is the word you use in relation to this work – can you elaborate?

Synchronicity is tricky. It’s like when you think of something you will spot it more often in the reality. I was also interested in this Native American Indian custom, that everybody has their own power animal. I was searching for what animal would be my power animal. After some research, I thought it might be the badger. Badgers are very rare animals in Poland, I’ve never seen a live badger in my life before, and while I was working on that project, I spotted 3 different badgers in only one month. Synchronicity is this kind of awareness, or a coincidence – if you prefer to call it that way. The peak was to meet a white albino deer in the woods at night. I stopped the car, photographed it with a small handy camera through a windshield and he walked away.

Is there anything you would have done differently?

I don’t know. Occasionally I still take some pictures in this style for that project. The project was noticed at some awards and festivals and in some magazines… but the book was never created, and I truly hope to find a publisher one day interested in making a quality photo book with this project. If so, a lot of unpublished images will be used in it. If I would start it today, I would show it to more trusted people first, before publishing it.

What/ Who would you most like to photograph that is perhaps ‘out of your reach’?

I consider myself a portrait and documentary photographer. Sometimes I work with well-known people or Polish celebrities. I really would like to do more portraits of faces everybody knows. For example, to work with world-famous actors. It’s fascinating how our perception works. I love faces and I love to gaze at faces. I can’t enough. Inside me, there is a little kid who is staring at you with [wide eyes] and [an] open mouth. I do a lot of street portraits of unknown strangers. This year I plan to go to Paris and see if I can create a body of street portraits that are connected only by location. I wonder if you would see a bunch of portraits from Paris and London you can tell the difference. Every city has its unique style and but also like [aiming to] freeze time how people look here and now. Even if it may seem simple portrait, after many years this kind of body of works reveals much more than then just a fashion. You see haircuts, makeup, accessories, phones, headphones, cars, or shop vitrine in the backgrounds, or posters behind on the wall. I like to think about pictures and how will they work 50 or 100 years from now. It’s a good exercise and I think the simplicity put in the right context will still amuse and wonder us.

What kind of response do you get about your work?

Well, that depends on the project of course. There are different reactions. Some are fascinated, some are disgusted, and others want to buy a print for a wall. The skulls are a kind of eternal symbol in art, literature, and movies. I did not discover it; it belongs to the visual heritage. These photos are just my small contribution to it. I wish more galleries would be interested in showing these types of projects.

Your work explores many styles–How do you transition between them?

Everything needs time. I used to have a problem with it. But then I realized that I just work that way. Every project has a different form because every project is about something different. I don’t know, maybe it will clarify more with time. But I’m not so young anymore (smiles).

Do you ever take risks in your approach?

I hope that I do so in every project. Even if many can see my works as a rather classic approach. But for every accepted form there are many unpublished, sometimes experimental attempts. Recently, I was growing mold on food scraps on an artificially sculpted face, for example.

Can you remember a specific moment that has stayed with you during your time working?

The albino deer mentioned above. I had some revelations in Africa. I’m fascinated by the people and the energy there. I spend one month in a monastery in the Central African Republic. I was disconnected from the internet and phone. And I was regularly meditating on a lonely rock near the monastery. It was a unique moment in my life. I miss this kind of peace and harmony. I’m easily distracted. I have a stream of ideas constantly flowing through my mind. It’s exhausting!

How do you read the people or situations you photograph?

I have about 20 years of experience as a photographer. I did a lot of very different things in photography. In the beginning, I was very interested in effective and beautiful pictures, the “wow” effect. Nowadays I think beauty is in the meaning or the understatement. Our imagination works much better than the author’s consciousness.

This an obvious question but what set you off on your chosen career path?

Coincidence. Or a few to be more specific. But it’s kind of boring and a long story. But as a teenager, I got a broken camera and at that time my brother was sharing an apartment in Vienna with an Austrian photographer. He fixed the camera, explained how the light meter works, and give me a few black and white film rolls. I still have those first negatives from Vienna.

Your interest in the ‘bad boy of French letters’ Michel Houellebecq caught my attention. He’s my favourite author.

Yes, I used to love his writings, I’ve read everything that was translated into Polish. I liked the roughness, exposing the truth about human behavior. Even if it’s a painful one, I like his uncompromising nature. At times, he’s able to touch upon everybody’s anxiety about how deranged we are living in the mass (of big cities) but having very few real connections. But to be honest, now I think I would choose Knausgaard over Houellebecq.

I’ve yet to read Knausgaard – what is it about his work you admire the most?

Well, I love the ways he writes, obviously. I mean, with ‘My Struggle’; the level of directness and kind of honesty is unique. I think he has a way of writing which is really ‘art’ to me. And also, his topics are kind of close to me. I can identify with his characters. I still like works by Houellebecq though, but at the same time, I think more and more he is kind of a product of clever marketing if you know what I mean.

What projects are you currently working on?

I always have several projects at various stages of development. Some of them will never be finished. I focus now more and more on portraits and on creating a unique and distinct style. Working on a new website to be more specific and defined as a photographer. It does not mean I will stop personal projects. I don’t think so.

I love and identify what you say, “the meaning or the understatement. Our imagination works much better than the author’s consciousness…” – Do you ever think there’s a point where artists can achieve that?

There are so many great artists, and so many ways of working, inspiration, waves, or impulses. I always try to do things better, and on one side I can be a control freak and on the other, I know that sometimes one has to let go… I’m still amused and surprised by the reality. Just a fine and tiny gesture can create a big masterwork. I’d compare it to sailing – when there is a right wind, for example.

What obstacles do you face the most as an artist?

I have so many doubts. It’s a lonely path. Every artist needs [sometimes] positive feedback, just to be sure their works mean something and that somebody does care about them. Or it makes somebody think. Times go fast, and because of how fast the information is exchanged today our brains are attacked with too much data. We are overloaded. Our perception can’t handle it properly. Small things you need to take care of can kill one’s ambitions.

How does an artist, or at least you, overcome the many doubts you mentioned? I find this a common theme amongst creative people.

I’d like to know that too. There are some lows and highs (or maybe I’m bipolar?!) Over the years I learned not to fight against the flow, I learned to use it. At the end of the day, as a wise man once said, inspiration is good, but it has to find you in the studio. And that means one should go to the studio regularly, and try to work, ‘nulla dies sine linea’ (no day without a line) – sometimes being in the studio and reading, thinking, or meditating is also a kind of work. And it belongs to the process.

Is there anything in art or the work you have produced that has taught you anything about yourself?

Sometimes when I’m processing a series of images after a shooting, at home, I clearly see that I should be more aware during a shoot – more aware of the subject, whether is it a person or not. To see things as they are and to react properly is the key. Photography teaches me that all the time.

Michal Korta, thank you.

Find out more about Michal Korta and his work on Lens Culture

You can also find him on social media:

His work and books are also available on Amazon