The argument for design providing solutions and art creating more problems is one I’ve never pondered nevermind dealt with in an interview situation. With Israeli designer-artist Noa Raviv, I was provided with such a chance to discuss, as pretentious as it may sound. Design by default seems to me to answer questions that at worst, tell lies, and at best, mostly prove unsatisfactory. Art is unambiguously seeking answers it may never find, and can often produce crap, but at least it passes time better and lets us marvel at the unexplained beauty where truths can be one day nailed on the head (perhaps only when dead).

In this interview with Noa Raviv, we discuss such themes and how philosophy may be the ultimate missing link between the designer and artistic approach. Naturally, we also discussed Noa’s varied work, personal life as a working mother, the Gaga Movement (Not Lady), creative processes, her use of technology in fashion, and how whilst working in New York provides opportunity, Israel will always be within.

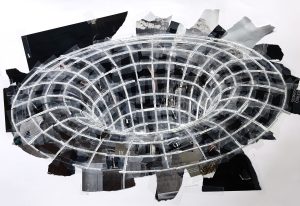

2020, Xerox print, hand-cut collage on paper

Noa, can you explain your approach to creation artistically? Boring start – the answer is never dull (no pressure).

My approach is pretty fluid. I love working with materials that change or decay over time—things that rust, melt, leak, or break down. I often jump between mediums—photography, collage, painting, performance, ceramics, metal, textiles, videos, and installations. When I get comfortable with something, I’m usually off to try another. It never gets boring, and there’s always a new challenge. I want to make things feel hybrid, in some state of flux.

It’s a standard question and I feel lazy all the time I ask it, but it’s always interesting – What are your biggest inspirations for being creative?

Literature, philosophy, math, chemistry, nature, and music. I might set some initial guidelines for a project like a scientist might, but then do my research with a speculative, playful “what if” mindset instead of sticking to strict methods and facts. In the studio, I embrace ‘not knowing.’ It’s about some kind of energy or force that’s hard to define, but tangible when it happens. I avoid anything that feels like a definitive answer. I don’t think you can really do that anywhere other than in art.

What made you move from fashion toward art, sculpture, paintings, etc?

I was looking for more freedom. In fashion, there was this need to be practical, to meet certain checkboxes, to follow the seasons. I think inherently, Design is about providing solutions, and the move toward art allows me to create more problems.

Art creates more problems, whereas design provides solutions? I’ve always believed that art was the answer, albeit a bloody long search and one which never (probably) ends. Can you expand more on how design fulfills you that art can’t? Does any piece of art satisfy you for answers at all – do you believe there can’t be any conclusions within art?

Yeah, maybe philosophy is the missing link. Or maybe, more broadly, language. I think art and design can mean different things to different people at different times. So I find it beautiful and hopeful to learn that people find answers in art or even conclusions! Maybe it’s just me who’s looking to get lost.

How has life growing up in Israel influenced your artistic and fashion designs?

It’s hard to pinpoint how Israel has influenced me, but I know it has, deeply. The harsh sun, the crumbling Bauhaus buildings of Tel Aviv, the salty waters of the Mediterranean, the informal brevity of the Hebrew language. The conditions of this country are so unique and difficult, beautiful and ugly at the same time. My former saxophone teacher, the late Erez Bar Noy, once said in an interview, “You can go west and east, north, and south, but in the end, Mom’s radio in the kitchen does the job and gets into the molecules of the soul.”

Israel is in my body now.

What made you relocate to New York?

I moved in 2015. Israel is a small place with a low ceiling and New York seemed like an adventure for a starting fashion designer. The energy of this city and its people still feels special.

I noticed you’ve lectured at the Glasgow School of Art. It interested me as I’m based in Glasgow. Can you tell me about that work and what your thoughts are about the city?

The Glasgow School of Art invited me to speak at a textiles conference a year after I graduated. I felt like a complete imposter surrounded by such brilliant, knowledgeable, and inspiring people. The school itself blew me away too—those looms, the history. I met some super-talented students too. The architecture of Glasgow is fabulous, the museums, the Mackintosh house. It was a really inspiring trip. During my visit, the Turner Prize exhibition was held at Tramway. I remember seeing Nicole Wermers’s fur coats draped over tube chairs and thinking that I’ve seen a coat on a chair so many times before yet I’ve never seen anything like that. It left a deep impression.

What does quality mean to you?

As time goes by, I believe more and more that quality hinges on honesty. It’s crucial to listen closely—to materials, myself, and the surroundings—even when it clashes with fears, ego, and ambition, to figure out what things genuinely want to express, to search for some truth. That’s the ultimate goal, the real fire.

What do you do to keep evolving, to keep being fresh in your work/ to keep reinventing yourself, so to speak?

I like reading and taking walks. It helps me think of things in a fresh way. I wish I had more time to read! And walk!

How has being a mother affected you and your output – priorities change – do you have time to work?

Like most mothers, my days are filled with disruptions—breastfeeding, school pickups, bedtime stories, meal prepping etc—so I end up working in these disjointed, brief bursts. Art critic Lucy Lippard captured this well in this essay that I really liked, “Issue and Taboo,” where she connects fragmentation and interruption to a feminine approach to art. She says, “Collage is born of interruption and the healing instinct to use political consciousness as a glue with which to get the pieces into some new order.” With my scattered schedule, I’ve learned to work on small bits at a time—little ideas that I can piece together later. It’s kind of like collage mode. It’s also a way to push back against rigid and linear structures. More like seashells less like a skyscraper.

How does being a mother influence your approach to work?

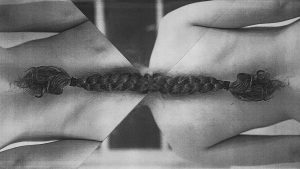

I often reference motherhood in my work, usually indirectly, using materials and small actions as conduits. For instance, my boys and I collect items like sticks and stones, which I later incorporate into my work. The act of finding them together imbues them with this special significance, talismanic, setting them apart from all the other sticks and stones in the world. I also keep the hair from our family haircuts. It is a potent material too, I can really feel its energy. My older son also comes with me to my studio sometimes. He’s a successful painter and an inventive ceramicist. I learn so much from his intuitive and playful way of making.

Can you describe your creative process from concept to finished piece?

Every work and project is totally different. Some works take ten minutes to make and others take years, some are well-planned while others are spontaneous. A common ground to everything is materiality. I seek to work with materials that have some energy. That energy doesn’t need to be visible or spark joy, it can come from the stuff’s past life, from how and where they were found, from their proximity to the body, or the language used to describe them. Writing is also a big part of my process. It’s a way to figure out feelings towards an object, an idea, or a way of working. For the impatient artist it’s faster to test a sculpture through words: Do I like the way engine oil and breast milk sound together? Cement and date syrup? Copper-plated playing card and a broken ruler? Often the description of objects and the way they feel on the tongue can have more weight than their visual appearance.

What role does technology play in your design process? I’m thinking the 3-D designs here.

That collection, which you are referring to, was created about ten years ago. It was a lengthy process packed with references, ideas, and attempts that slowly led to its creation. I began my research with Greek sculptures, contemplating their evolution over time and how they were copied and replicated so often throughout history that something so masterful as these marble statues, became merely a cheap plastic souvenir—an empty repetition of style and expression. With these ideas in mind, I reflected on our era and how objects, clothes, and works of art are endlessly copied until the origin loses its meaning.

I was also taking 3D software classes. While I was fascinated by the endless possibilities of 3D printing, I was more intrigued by the software itself—the grid and the way three-dimensional objects are represented on a flat, two-dimensional computer screen, virtually depicting volume in an almost tangible way. But what captivated me the most were the errors—when the computer failed to execute a command, generating strikingly beautiful and mysterious virtual objects. I fell in love with the uniqueness of those glitches and started creating them deliberately. Each error looked different from the others, completely unexpected, yet made and organized by an algorithm.

Mistakes have a unique quality—first, because no one wants to copy them, and second because it is impossible to recreate the same mistake twice. In today’s world, where everything is copied and reproduced, mistakes have the potential to be truly original and one-of-a-kind.

How do you see the relationship between art and fashion in your work?

To me, two main things define fashion: how elements are combined and their relationship to the present moment. Even though I no longer create clothing, these principles still drive much of my process. Fashion, for me, is about intuitively listening and responding – It’s like making a collage with the right materials and the right glue at the right time.

What makes you laugh or despair?

My kids make me laugh daily. The state of the world is pretty depressing. The list feels endless. I wrestle a lot with the meaning and role of art, facing all these catastrophes, but I want to believe that art can provide light, love, and a sense of ambiguity. It may not reshape the world, but it can touch hearts and offer small pockets of hope.

Do you want to share anything on your upbringing, instinct for your profession, and your career path which I won’t find on Google?

I love to dance and regularly practice Gaga which is a movement language and improvisational technique created by choreographer Ohad Naharin for his Batsheva Dance Company. It is physical yet focuses on internal sensations. It has changed my life and I recommend it to anyone!

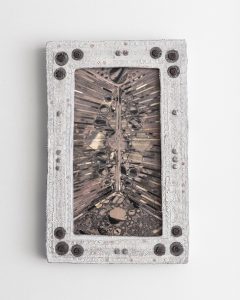

2022. Chemical reaction of nipple cream, honey, and darkroom chemicals on a light-sensitive paper, set in a glazed ceramic frame.

Is it difficult to be successful in your profession and have you always had the belief, the instinct that you are what you do? I mean that in the sense of Christopher Hitchens, who time and time again said being a writer, for him, isn’t a profession, its what he IS….

It’s probably true for a lot of creators, it really is who I am. As a kid, I’ve always drawn, painted, made collages, cut up my grandmother’s textiles to sew with a stapler, and there has always been some creative outlet to channel my energy into. As much as I like getting lost in my work, without it, I’d be truly lost.

2020. Hand cut collage, page from a dictionary of military terms

Looking back, is there a particular piece or project that holds special significance to you?

My first fashion collection. It was the first time my work got exhibited in the US, with pieces shown simultaneously at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and The Met—something I had never even dreamt would happen. I’ll always be super grateful to everyone who helped me in the making of those pieces and to the institutions that took a chance on me early on. Those moments really shaped how I see art, design, and the very essence of exhibitions…

What’s next for you?

Writing. It’s a slow process, but I hope in the next few years to publish some texts I’ve been working on. I’m writing a novel and an essay about motherhood and art-making.

Noa Raviv, thank you so much.

Keep up to date with the work of Noa Raviv via her online presence!