I wish I had hours or months to speak to Wim Wenders. This is the guy who made the majestic Wings of Desire among many others. Paris, Texas is another which demands the attention of all.

Wim Wenders came to international prominence as one of the pioneers of German Cinema during the 1970’s. Quite rightly, he is now considered one of the most important figures in contemporary film and for me, is a cinematic legend. In addition to his many prize-winning feature films, his work as a scriptwriter, director, producer, photographer and author also encompasses an abundance of innovative documentary films.

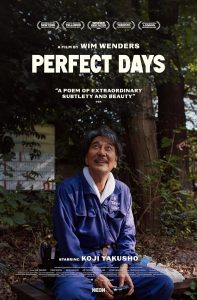

His new film, Perfect Days, takes the seasoned writer-director to Tokyo to tell a story celebrating the hidden joys and minutiae of Japanese culture.

In a deeply moving performance that won the Best Actor award at Cannes 2023, Koji Yakusho (Babel, 13 Assassins) stars as Hirayama, a contemplative middle-aged man who lives a life of modesty and serenity, spending his days balancing his job as a dutiful caretaker of Tokyo’s numerous public toilets with his passion for music, literature and photography. As we join him on his structured daily routine, a series of unexpected encounters gradually begin to reveal a hidden past that lies behind his otherwise content and harmonious life.

I had the absolute pleasure of talking to Wim Wenders about his new movie, aptly titled, Perfect Days.

Perfect Days marks your return to Japan. How did it come about?

The film came as a surprise letter early last year. “Would you be interested in shooting a series of short fictional films in Tokyo, maybe 4 or 5 of them, about 15 to 20 minutes each? These films would all deal with an amazing public social project, involve the work of great architects and we would ensure you could develop the scripts yourself and get the best possible cast. And we’d guarantee you have total artistic freedom.” That sounded interesting, to say the least. For years already, I was longing to go back to Japan and had real attacks of homesickness for Tokyo. So, I read on: the subjectwould involve public toilets and the hope was to find a character through whom one could understand the essence of a Japanese welcoming culture, in which toilets play a whole different role than in our own Western vision of “sanitation”. For us, indeed, toilets are not part of our culture, on the contrary, they are the incarnation of its absence. In Japan, they are small sanctuaries of peace and dignity …

I liked the photos I saw of those marvels of architectures. They rather looked like temples of sanitation than toilets. I liked the idea of “art” linked to them. And I certainly liked to see them in a fictional context. I always feel that “places” are better protected in stories than in a non-fictional context. But I didn’t like the idea of a series of short films. That is not my language.

Instead of shooting 4 times 4 days, I answered, why wouldn’t we shoot a real film in these 17 days. What can you do with 4 short films, anyway. Imagine you had a long feature film instead! The answer was: we love your idea! But can it be done? I wrote back: Yes! If we reduce our story to fewer locations and to one leading part. But first I’d have to come and see for myself. I cannot imagine a story without knowing the places for it. And I am in the middle of a shoot. I can give you a week in May and then we can possibly do it in October, when I would have a window in post production from that other film. (Which was Anselm, in its second year already and in the editing room. All shooting for it was done.)

I ended up traveling to Tokyo in May for 10 days. I was able to meet my dream cast for the possible role to be written, Koji Yakusho. (Whom I’d seen in a dozen of movies and always admired.) I saw these places, all of them located in Shibuya that I love. These toilets were too beautiful to be true. But they weren’t what this film was going to be about. This could only become a movie if we managed to create a unique caretaker, a truly believable, real character.

His story alone would matter, and only if his life was worth watching, he could carry the film, and those places, and all the ideas attached to them, like the acute sense of “the common good” in Japan, the mutual respect for “the city” and “each other” that make public life in Japan so different to our world. I couldn’t possibly write this on my own. But I had a great sparring partner and co-writer in Takuma Takasaki. We dug deep to find our man …

The film describes in an almost poetic way the beauty of the everyday through the story of a man who lives a modest but very content life in Tokyo.

Yes, all of that is true. But it all came out of Hirayama. That’s what we decided to call this man who slowly took shape in front of our inner eyes. I imagined a man who had a privileged an rich past and who had fallen deeply. And who then had an epiphany one day, when his life was at its lowest point, watching the reflection of leaves created by the sun that was miraculously shining into the hellhole he was waking up in. TheJapanese language has a special name for these fugitive apparitions that sometimes appear out of nowhere: “komorebi”: the dance of leaves in the wind, falling like a shadow play onto a wall in front of you, created by a light source out there in the universe, the sun. Such an apparition saved Hirayama and he chose to live another life, one of simplicity and modesty. And he became the cleaner who he is in our story. Dedicated, content with the few things he has, among them his old photo camera (with which he only takes pictures of trees and komorebis), his pocket books and his old cassette recorder with the collection of cassette tapes he saved from his younger days. His choice of music also informed us about our title, when Hirayama (on the script already) one day listens to ‘Perfect Day’ by Lou Reed.

Hirayama’s routine became the backbone of our script. The beauty of such a regular rhythm of “always the same” pattern of days is that you start seeing all the little things that are not the same and change every time. The fact is that if you indeed learn to entirely live in the here and now, there is no more routine, there’s only a never-ending chain of unique events, of unique encounters and unique moments. Hirayama takes us into this realm of bliss and contentment.

And as the film sees the world through his eyes, we also see all the people he encounters with the same openness and generosity: his lazy co-worker Takashi and his girlfriend Aya, a homeless man living in a park where Hirayama works every day, his niece Niko who seeks refuge at her uncle’s place, “mama”, the owner of a modest little restaurant where Hirayama goes on his free days, her ex-husband and many others.

What is it about Japan and its culture that holds such fascination for you?

“Service” has a whole different connotationin Japan than in our world. At the end of the shoot I met a famous American photographer who couldn’t believe I had made a film about a man who cleaned toilets. “That’s the story of my life!” he said. “When I came as a young man to Japan to learn martial arts, the famous teacher I went to said to me: “If you work in public toilets for half a year, cleaning them every day, then you can come back and see me. That’s what I did. I got up every day at 6am to clean toilets, in one of the poorest districts of Tokyo. The teacher followed that from a distance and took me up as a student afterwards. But up to this day, I still do it for a week, every year.” (The man is now in his sixties and has never returned to America.) Anyway, that is just an example. There are other stories of heads of big companies who gained the respect of their workers only after they arrived at work before them and cleaned the common toilets. This is not “inferior” work. It is rather some form of spiritual attitude, a gesture of equality and modesty.

And then you only have to live shortly in America to understand the importance of “The Common Good”. Once during a long stay in Japan, when I was working there on the dream sequences of Until the End of the World I received the visit of an American friend who had never been to Japan before. It was winter time and many people ran around with masks. (30 years before the pandemic.) “Why are they all so scared to catch a bug?” my friend asked me. I told him: “No, not at all. They have a cold already, and they wear masks to protect the others:” He looked at me in disbelief. “No, you’re kidding!” They were not, that is a common attitude.

You have a long association with Tokyo and Japan. Tokyo itself plays an important role in Perfect Days, because you had the extraordinary chance to shoot in places where it is usually not allowed to shoot. How was the experience of shooting in Tokyo? And how has Tokyo changed since Tokyo-Ga?

I loved Tokyo the first time I ever wandered around there and got lost. That was already in the late seventies. It was a time of sheer wonder. I’d walk around for hours, not knowing where I was in this huge city, then just step onto any subway and find my hotel destination again. Every day I went into another area. I was amazed by the seemingly chaotic structure of he city where you would find old blocks with ancient wooden houses next to skyscrapers and busy intersections, where you’d walk under these science-fiction double- and triple decker freeways and find the most peaceful living areas and mazes of tiny streets right next to them. I was fascinated by all the future I could see shaping up. Then, I had always seen the United States as the place to encounter the future. Here in Japan I found another version of the future, one that suited me really well.

And then, of course, I was informed through the films of Yasujiro Ozu (who is still my declared master, even if I only got to see his work when I was already a young filmmaker with several films under his belt.) He had given us an almost seismographic account of the changing Japanese culture from the twenties to the early sixties when he died. Tokyo-Ga I made in 82 on his traces, trying to see how Tokyo had already changed since he last shot there 20 years earlier.

\

You are famous for integrating music into your films in a very special way. Now in Perfect Days you have come up with a very special music concept.

It seemed wrong to conceive of a “score” for this simple everyday life. But as Hirayama listens to his cassettes of music from the sixties through to the eighties mostly, his musical taste gave us a soundtrack of his life, from the Velvet Underground, Otis Redding, Patti Smith, the Kinks or Lou Reed to others, also to Japanese music from that period.

You dedicate the film to the Yasujirō Ozu (Tokyo Story). Why is he important to you?

Mostly the feeling that permeates his films that every thing and every person is unique, that every moment is happening only once, that the everyday stories are the only eternal stories.