Seamus Murphy and PJ Harvey began their collaboration back in 2008, when the latter saw an exhibition and book of Murphy’s on his work ’A Darkness Visible’. Seamus would later shoot short films for PJ’s demo of ‘Let England Shake’ and the artistic bond evolved from there.

In 2016 Harvey released ‘The Hope Six Demolition Project’, recorded on public display at Somerset House and influenced by the exploration she and Murphy embarked upon together.

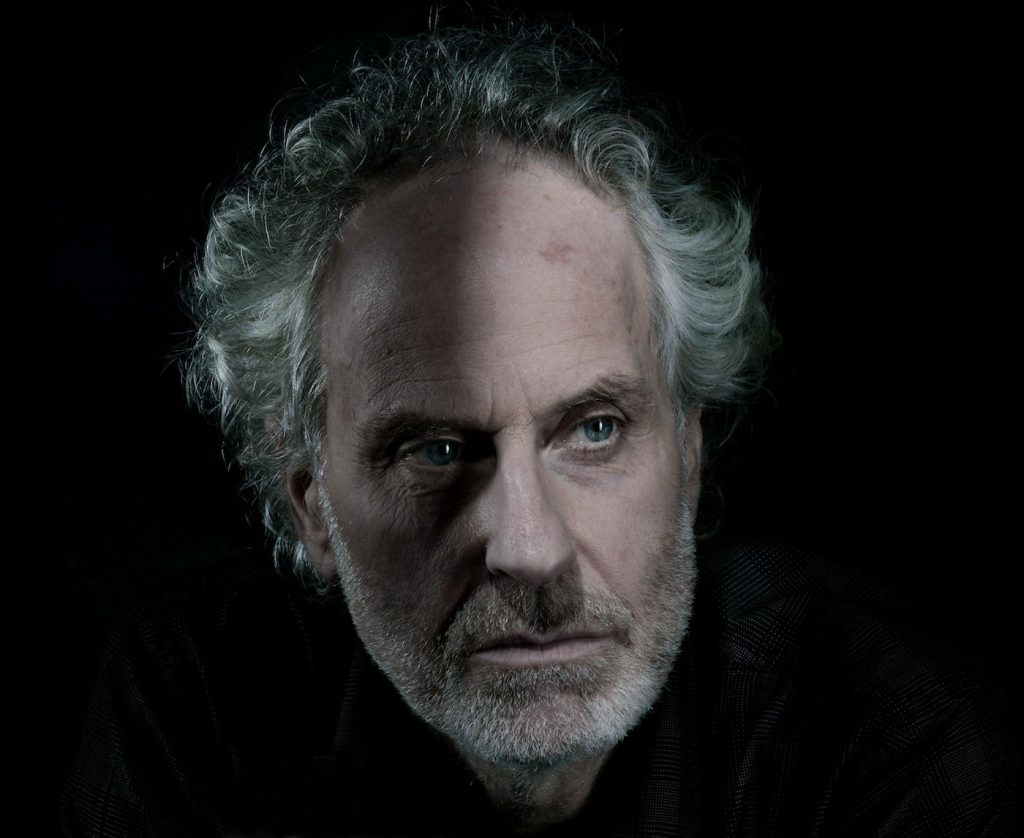

‘A Dog Called Money’ is a an extension of that recording and documents such travels. In a lengthy, often hilarious, conversation with Seamus Murphy, we discuss his work as a photojournalist, his work with PJ Harvey, dealings with the Trump people, as well as the themes and importance of their new film.

Oh, and Seamus often refers to Ms Harvey as ‘Polly’, so I will do too. When in Rome, or Kosovo.

Before we get onto the really serious chat, first of all it seems proper to ask about your health as you’re recovering from a car crash?

I fractured my spine so yeah it was a bad one, but no one got killed, thank fuck. I was travelling from a film festival in Kosovo. Myself and my wife were driving to Montenegro for a few days holiday and it [happened] on our first day driving… and that was the end of the holiday. We were in hospital for weeks in Albania and when we eventually came back to London I wasn’t allowed to climb stairs for another 3 weeks.. they [doctors] tell you not to sit down as well so it was a case of lie down or stand.

And you were in recovery while still working?

I had made a short film for Channel 4 news and I had an idea to do something about the Afghan-soviet invasion of Afghanistan which happened 40 years ago. I was going to edit over the summer but I had the crash and literally wasn’t being able to get back to it until recently. If I was doing this with my normal editor it would have taken a long time, but it had to be done in 5 days and it was all in Russian, so it was an absolute fucking whirlwind but we got it. I spent a lot of time in the edit standing up. They had these tables you could elevate so I was standing, others sitting .. but I’m very much on the mend and just happy to be alive.

‘A Dog Called Money’ focuses on a few key places – Washington > Kosovo > Afghanistan with the recording of ‘Hope Six…’ at Somerset House coming in and out – why these particular settings?

These are places I know from my work. I had made some short films for Polly’s ‘Let England Shake’, after she had written the songs. That album was a first step in her writing largely about the world beyond herself, and she focussed on England. This project was an extension of that process but to go beyond the familiar, this time around we wanted to try to do something that in real time we were experiencing at the same time. I have been going to Afghanistan since 1994 covering the situation there, I worked in Kosovo in the late 90’s and returned in 2004. Both of us had worked in DC before, me taking photographs and her doing gigs. In fact she was staying in a hotel across from the Pentagon when the 9/11 attacks happened. But neither of us had been outside the usual, central parts and we learned about Anacostia and heard that it represented another side of DC and America, so we decided we would go there too.

The film has a lot going on – the very public recording of Polly’s ‘Hope Six…’ as well as themes on politics and religion, two great subjects. Is this purely subjective or are you putting your own messages in there?

Absolutely not, I’m not thank kind of person, I’m not that kind of journalist, or photographer or film maker or whatever. Ofcourse there are messages [in there] but I’m not burying messages. I’m not setting out to preach a message. The thing is that these places fascinate me and the people I met are people that I really wanted to get to know and I wanted to try to learn more about them and try and tell their story. Obviously there are many elements to this film. You could cut it in half – I dunno what the proportion is. But you’ve got Somerset House [where the album recording took place], and you’ve got these other places so right there you’ve got 50% to do justice to something, then you’ve got the rest.

And on the films themes or direction?

I was trying to understand and communicate what it’s like with someone like Polly. It could be any artist being inspired and then transmitting that into their work and it is fragmented, you know? You’ll get a sentence from one guy, you have a tree in Kosovo, a pub fight in DC, and that might be a song. Obviously Polly was inspired in some songs, for example while in Afghanistan, but you can be sure there are lines in a song from Afghanistan that she would have found on the road when she was touring or even just being in Dorset. In terms of the religious thing, each of those places are all religious. It just so happened that two were Christian and one was Muslim but if I were to turn the corner and found a synagogue and it was interesting then you could be sure it would have been in there. It wasn’t in any kind of way deliberate. If there had not been religion I wound’t have inserted it, I wouldn’t have gone looking for it. If you’re in Washington DC and you’re in a black neighbourhood, there are a number of things that are absolute standard things, like barber shops and churches. If you go to Ireland, its pubs.. and churches. This film, in many ways, is many years of my life before I met Polly. I’d been going to Afghanistan since 1994, Kosovo in the late 90s. This goes back a long way.

You worked and have worked in some places where major conflict seems standard to Western types – do you prefer these types of environments and how does that impact you emotionally, or the artistic output?

It’s not that I prefer conflict environments – they can be harrowing and dangerous places to be – but they are places where change is happening and history is being made. I work as a journalist when I am in these places, art may or may not come from it. Either way I have a function when I am there, to record what I am seeing and try to understand it to communicate it. Depending on how severe the circumstances, to some degree that role can protect you. But being human means your emotions will always be involved and situations and images stay with you long afterwards.

It seems that during work for ‘A Dog Called Money’, you must gather so much material that some great stuff will get cut or even lost?

Lots, theres so much. I still say to people that I really wanna do a separate piece. Maybe its an instillation, maybe its not a film. With Somerset House, I’ve got weeks of stuff from everyday, where we were shooting 5 hours everyday over 5 weeks, 6 days a week. Theres a ton of material, music, a ton of discussions and a lot of funny and interesting stuff and it couldn’t end up in a 90 minute film.

Therefore the editing process must have been difficult..

We were sort of guided, myself and the editor, by the music and the strongest material is the stuff that inspired Polly to write. When I started out making the film I wasn’t convinced that it was gonna be about the album, or that the album was in any way central but it became like that to me. An album is a very iconic thing, a cultural phenomenon and when she chose to record it in a bonkers way, I think it kind of wrote itself. It’s a really nice way to bring that experience, to put it down somewhere and bring it to life, that and of course the contrast of that with being in rural places, sometimes impoverished, but very rich in their own way. And then you go to this very anti septic very structured interior [Somerset House] where she even tells people not to even put fucking coats on the back of seats. That’s funny. The thing that gets me is sometimes when I’m sitting in an audience during the film and I’m thinking ‘why aren’t you finding this funny?’Are people worried that they shouldn’t be laughing? Life is pretty funny and you can either laugh at it or you can fucking cry.

Working with someone like Polly must make it easier, her status that comes with it must add to the direction of such a project..

She’s a star but that was never the relationship that we had. In fact I had never even heard her music when she got in touch with me to suggest working together back in 2008. I’d heard of her, and I’d seen her on television and I’d seen her picture but I’d never heard the music or be able to say ‘thats a PJ harvey song’. We were always equals and as soon as I met her I met a very genuine person. When she handed me the ‘Let England Shake’ demo I was fucking knocked out, because she was describing front lines and places that are in conflict that I’m familiar with. She had never been to those places yet she was nailing it. So for this project I thought, ‘yeah, I definitely want to go travelling with this person’, because she’s gonna come back with some amazing things, things that even I wouldn’t have seen, or described in the way she does. When we started out I wasn’t even sure I should be filming her, thinking was I gonna be annoying her in doing so. It was half way through shooting in Kosovo when I thought ‘I better get some footage cos someone out there might be interested in seeing this’.

Polly chose an interesting way of recording ‘Hope six..’ by allowing the public to bear witness to an extent?

Polly suggested this idea to her manager. She said she wanted to make the record a different way. And I had no intention of recording them making the album, I thought thats what everyone does – “I don’t wanna do THAT”. Then I started hearing the conversations she was having with John Parish and Flood (producer), hearing things like ‘this approach could be interesting and I’ve no idea how its gonna turn out’. So I went along for the first few days [of recording] and stayed for 5 weeks. When we were travelling she was always taking notes, as well as writing a book while I’m also taking pictures which became a book. So for me maybe the film was never gonna be made and we were just gonna do a book. The book was very important to us as well. I think when people see the movie they’ll think this was all planned with a big budget. I had no money, there was no budget for this. The first bit of money that went to this was when we started editing the film. I shot everything on the back of my own other work.

What’s your take on the criticism thats been levelled on your approach?

It’s funny I read some comments from people where they talked about ‘privilege’ – there’s no fucking privilege here! I’m a working photographer. If it’s a privilege to work, then I’m privileged, but I’m not doing this as some kind of past time, this is my work. You know, fuck off, this is my work!

What do you think about the term ‘Poverty safari’ which has been used as a criticism…

Yeah i’ve read that too and you know… I didn’t go out and seek out people that were poor. Some of these places, some of these people, weren’t poor. The people I found in DC were more impoverished, I found, in terms of their future and their hope. The way some of them see the world is pretty impoverished. None of the people I filmed were hungry, they were spending their money on drugs or drink but not short of money, so I don’t know where the poverty is. The idea of this being about that or we were exploiting poverty in some way, I don’t get that, I don’t see it. I’ve been a journalist for over 30 years, I’ve travelled the world and these to me are places that are just life. It baffles me, just like it baffles me that this is some sort of indulgence and privilege. When it came to Polly… the thing is Polly could have written an album about or with similar themes and not have left London, or not have left Dorset. Would that have made people happy? Why would that have been better? I mean that would have been less sincere, less genuine. That would have been indulgent, perhaps. And I’m not criticising, artists can do whatever the fuck they like… that’s supposedly what art is about. This censorship which says ‘you shouldn’t be doing that, you shouldn’t be going to those places, you shouldn’t be showing those things’, why not? And who’s telling us this and on what basis, and who are they to say so. People are entitled to their opinions. But am I not entitled to my opinion? The film might never have been made, would that have been better? and Polly might never have seen Afghanistan, would that have made those people happy?

Is it fair to say this is discovery project?

As a journalist I’ve tried to go to places with an open mind. I didn’t wanna go to Iraq, or Afghanistan thinking ‘I wanna show these people being abusive to women, or I wanna show these people being cruel and I wanna show that the Taliban are bad guys’. I wanted to go and talk to people, to go and find out what was happening in those places and I wanted the work to reflect that discovery. There is some decision making but I like to be surprised, and I like to learn something.

As opposed to setting everything out beforehand, or writing a plan of action – What does your approach bring to ‘A Dog Called Money’?

Television is very good at the other approach. They go like ‘we’ll set out the story, at the beginning, we’ll find a bit of drama and we’ll then resolve it’. That was not what I wanted to do. As I went along I was thinking Polly’s gonna record in a studio when she doesn’t know how it’s gonna go because she hasn’t done it before. And none of us had ever really done this before and people are gonna be watching and there’s 10 musicians and they’re all battling with their egos, and they’re all trying to contribute to this album, and they don’t wanna fuck it up, and yet they’re being watched. If there are such things as ‘viewers’, I’d like to challenge them to sort of say, ‘this is not a riddle, it’s not obvious whats gonna happen next’. It’s like when you go travelling on like a package holiday you might know what comes next. This is not a package holiday, if you want to go see a package holiday… erm, you can name that film, but if you wanna go travelling then see ‘A Dog Called Money’.

Back to the parts shot in DC – Trump town – tell me about that and the Trump rally

Yeah I was doing stuff for actually another project as well as this one and I was able to afford to be there, like I say there was no production money for this film. I was doing other things and some of that was covering the election. It was easy to get in with the Bearnie Sanders people, very easy to get in with the Hilary Clinton people. But Trump was fucking hard, he hated the press, and I wasn’t fully accredited to the New York Times for example or whatever, so I managed to go to a weird office of the Trump campaign in some weird place in Pensilvania and I met this guy from Alabama, a young guy, and we got to talking. He was like ‘what are you doing’ and I said I really want to cover what your message is. He looked at my website that night and called and said “Ok you’ve got to cover this, you’ve got to cover a rally”, and I was like “Well yes of course I’ve gotta come” and then he was saying “I’m the guy who’s gonna do it”. And of course I said “Yeah you’re the guy who’s gonna help me” and he fucking did! He got me in.

He was very friendly. I didn’t think too deeply into his politics and I think it would have been pretty ugly, but I managed to get access using journalism. You use whatever skills and charm you have to get into places to find out whats going on, that’s what was going on at that point. ‘A Dog Called Money’ could refer to much of what the Trump people are about, the rich get richer etc… many many things.

And it became relevant to the finished film.. Fine timing.

As soon as he got in, he started talks with the Taliban, it was all a highly relevant development to the world. It seemed to be really appropriate for the film, it seemed, in a way, again, not intended. We didn’t know Trump was on the rise when we started on the project, but it seemed to be a climax, certainly in the film it seemed a bit of an explosion. With the album and the book we did, again there was no plain messages but there was this drum beat in the background, and the drum beat sort of ends with populism, unfortunately, and Trump, the guy in Hungary and fucking Boris Johnson, Brexit and Farage and the rest.

What do people see in the likes of Trump, the ‘populist’ movement?

Oh…I suppose… it’s hard to know because for some in America it could be because ‘you’re rich, you’re happy, you wanna hang on to yourself’. Maybe it’s just that you don’t wanna pay taxes, or big taxes. Maybe it’s ’keep the Mexican wetbacks out of America’ , ’he’s gonna build a wall’ etc. Maybe they just see that. Maybe it’s people who’ve lost their jobs and they look at China and they think ‘Fuck all these people who are getting our jobs, this guys telling us he’s gonna reinvigorate the coal industry and the steel industry’. Ofcourse he fucking isn’t. It’s like Boris Johnson or Farage, they’re not gonna create this ‘Great’ Britain again by leaving Europe but there are people out there who are disaffected, you know? They got slated by Regan, they got shafted by Thatcher and here’s the guy who’s gonna help them. The fact that he was a billionaire, the fact that he was brought up a millionaire, the fact he’s a useless businessman and he lies and he cheats, unfortunately doesn’t seem to matter, like with Boris Johnson. I mean do you believe a word that fucking guy says? it doesn’t seem to matter.

On sunnier subjects – I understand you’re now working on a project about your home town and a particular poet?

I am working on a documentary film about Dublin, revolving around one character. It’s about a poet called Pat Ingoldsby. He’s like an irish version of Spike Milligan, an absurdest, a very surreal, very brilliant guy who’s had his own battles and mental health issues, depression, as a lot of brilliant genius have. He underwent electric shock therapy in the 70s and he’s written amazing poems about this stuff.

He was also a kids TV presenter?

He had this very strange role. He managed to infiltrate RTE and got a job as a children’s entertainer but adults would watch as he’s so funny. And then suddenly one day he disappeared and he was on the street, not living, but on the street selling his poetry and he became a self publishing poet. The poems are amazing but because he’s sort of unruly and brilliant every year he’ll produce a new book, but he edits it himself, so really brilliant work will inevitably be mixed in with lesser works. The film is kind of a look at him and a chance to edit and present his work. To me he’s like the eyes to the streets of Dublin, like a great chronicler of the last 30 years of Dublin. I’m trying to do something that would look at Dublin as much as him, but through his eyes at the same time. The only shop he sells his books in is the hardware shop down the road from him. He loves the fact you can go into ‘Nolans’ and buy nails and a hammer and a book of poems, that’s really useful ha. He’s someone who was never quite recognised for the poet and artist that he is so this is an opportunity to put him on the map.

Photography is your main focus – what does photography provide for you that poetry, music or film cannot?- At what time in your life did you know for certain that you wanted to capture still moments?

Photography was my entry into a lot of things – international politics, society and everyday life around me, the wider world. It has its own language and is very personal. At times its a very solitary activity- which it probably shares with poetry, less so filmmaking. As soon as I started printing my own work in a darkroom the connection was made with the camera I was using and the world I lived in – and thats when I realised this was what i wanted to do.

‘A Dog Called Money’ is out now and available on MUBI