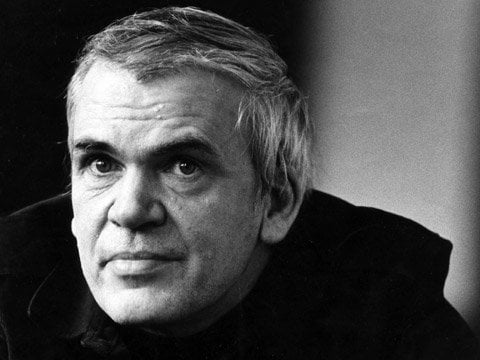

Milan Kundera (1929-2023) specialized in writing about philosophy, women, memory, love, sex, life’s absurdities, melancholia, betrayal, loss, communism, nostalgia, and most importantly, sex, lust, love, and women. At this current moment, with the loss of this most life-changing of authors (for me at least), I’m struggling for words to summarise his importance. Rather, I’ll just let you sample the greatest and profoundly heart-breaking passages yours truly has ever read. And yes, for those reading who know me, it involves the death of a dog.

“Dogs do not have many advantages over people, but one of them is extremely important: euthanasia is not forbidden by law in their case; animals have the right to a merciful death. Karenin walked on three legs and spent more and more of his time lying in a corner. And whimpering. Both husband and wife agreed that they had no business letting him suffer needlessly. But agree as they might in principle, they still had to face the anguish of determining the time when his suffering was in fact needless, the point at which life was no longer worth living.

If only Tomas hadn’t been a doctor! Then they would have been able to hide behind a third party. They would have been able to go back to the vet and ask him to put the dog to sleep with an injection.

Assuming the role of Death is a terrifying thing. Tomas insisted that he would not give the injection himself; he would have the vet come and do it. But then he realised that he could grant Karenin a privilege forbidden to humans: Death would come for him in the guise of his loved ones.

Karenin had whimpered all night. After feeling his leg in the morning, Tomas said to Tereza, “There’s no point in waiting.”

In a few minutes they would both have to go to work. Tereza went in to see Karenin. Until then, he had lain in his corner completely apathetic (not even acknowledging Tomas when he felt his leg), but when he heard the door open and saw Tereza come in, he raised his head and looked at her.

She could not stand his stare; it almost frightened her. he did not look that way at Tomas, only at her. But never with such intensity. It was not a desperate look, or even sad. No, it was a look of awful, unbearable trust. The look was an eager question. All his life Karenin had waited for answers from Tereza, and he was letting her know (with more urgency than usual, however) that he was still ready to learn the truth from her. (Everything that came from Tereza was the truth. Even when she gave commands like “Sit!” or “Lie down!” he took them as truths to identify with, to give his life meaning.)

His look of awful trust did not last long; he soon laid his head back down on his paws. Tereza knew that no one ever again would look at her like that.

They had never fed him sweets, but recently she had bought him a few chocolate bars. She took them out of the foil, broke them into pieces, and made a circle of them around him. Then she brought over a bowl of water to make sure that he had everythng he needed for the several hours he would spend at home alone. The look he had given her just then seemed to have tired him out. Even surrounded by the chocolate, he did not raise his head.

She lay down on the floor next to him and hugged him. With a slow and laboured turn of his head, he sniffed her and gave her a lick or two. She closed her eyes while the licking went on, as if she wanted to remember it forever. She held out the other cheek to be licked.

Then she had to go and take care of her heifers. She did not return until just before lunch. Tomas had not come home yet. Karenin was still lying on the floor surrounded by the chocolate, and did not even lift his head when he heard her come in. His bad leg was swollen now, and the tumour had burst in another place. She noticed some light red (noy blood-like) drops forming beneath his fur.

Again she lay next to him on the floor. She stretched one arm across his body and closed her eyes. Then she heard someone banging at the door. “Doctor! Doctor! The pig is here! The pig and his master!” She lacked strenth to talk to anyone, and did not move, did not open her eyes. “Doctor! Doctor! The pigs have come!” Then silence.

Tomas did not get back for another half hour. He went straight to the kitchen and prepared the injection without a word. When he entered the room, Tereza was on her feet and Karenin was picking himself up. As soon as he saw Tomas, he gave him a weak wag of his tail.

“Look,” said Tereza, “he’s still smiling.”

She said it beseechingly, trying to win a short reprieve, but did not push for it.

Slowly she spread a sheet out over the couch. It was a white sheet with a pattern of tiny violets. She had everything carefully laid out and thought out, having imagined Karenin’s death many days in advance. (Oh, how horrible that we actually dream ahead to the death of those we love!)

He no longer had the strength to jump up on the couch. They picked him up in their arms together. Tereza laid him on his side, and Tomas examined one of his good legs. He was looking for a more or less prominent vein. Then he cut away the fur with a pair of scissors.

Tereza knelt by the couch and held Karenin’s head close to her own.

Tomas asked her to squeeze the leg because he was having trouble sticking the needle in. She did as she was told, but did not move her face from his head. She kept talking gently to Karenin, and he thought only of her. He was not afraid. He licked her face two more times. And Tereza kept whispering, “Don’t be scared, don’t be scared, you won’t feel any pain there, you’ll dream of squirrels and rabbits, you’ll have cows there, and Mefisto will be there, don’t be scared…”

Tomas jabbed the needle into the vein and pushed the plunger. Karenin’s leg jerked; his breath quickened for a few seconds then stopped. Tereza remained on the floor by the couch and buried her face in his head.

Then they both had to go back to work and leave the dog laid out on the couch, on the white sheet with tiny violets.

They came back towards evening. Tomas went into the garden. He found the lines of the rectangle that Tereza had drawn with her heel between the two apple trees. Then he started digging. He kept precisely to her specifications. He wanted everything to be just as Tereza wished.

She stayed in the house with Karenin. She was afraid of burying him alive. She put her ear to his mouth and thought she heard a weak breathing sound. She stepped back and seemed to see his breast moving slightly.

(No, the breath she heard was her own, and because it set her own body ever so slightly in motion, she had the impression the dog was moving.)

She found a mirror in her bag and held it up to his mouth. The mirror was so smudged she thought she saw drops on it, drops caused by his breath.

“Tomas! He’s alive!” she cried, when Tomas came in from the garden in his muddy boots.

Tomas bent over him and shook his head.

They each took an end of the sheet he was lying on, Tereza the lower end, Tomas the upper. Then they lifted him up and carried him out to the garden.

The sheet felt now wet to Tereza’s hands. He puddled his way into our lives and now he’s puddling his way out, she thought, and she was glad to feel the moisture on her hands, his final greeting.

They carried him to the apple trees and set him down. She leaned over the pit and arranged the sheet so that it covered him entirely. It was unbearable to think of the earth they would soon be throwing over him, raining down on his naked body.

Then she went into the house and came back with his collar, his leash, and a handful of the chocolate that had lain untouched on the floor since morning. She threw it all in after him.

Next to the pit was a pile of freshly dug earth. Tomas picked up the shovel.

Just then Tereza recalled her dream: Karenin giving birth to two rolls and a bee. Suddenly the words sounded like an epitaph. She pictured a monument standing there, between the apple trees, with the inscription Here lies Karenin. He gave birth to two rolls and a bee.”