“I run every day, running is like an amplifier of presence for me, a time to reconnect with myself and the world. The sound of footsteps and breathing already creates music and incites the beginning of a dance.” Olivier De Sagazan.

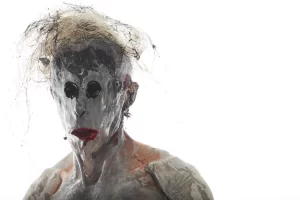

Olivier De Sagazan blurs the lines between sculpture, painting, and performance, between surrealist dreams and your worst anxiety-ridden nightmares. The phrase ‘the art of decline‘ easily comes to mind when I look at his work. However, I’m told this observation is somewhere between cliche and ‘old hat’ when I put this to De Sagazan himself. I’m delighted to be told I’m wrong even though I’m correct! What cannot be denied, however, is that De Sagazan uses himself and others as a canvas, vehicles for expression. For me, De Sagazan recalls some of filmmaker David Cronenberg’s most complex ‘body-horror’ material, and the more I look through his creations, the more I find cinematic splendor. – namely, Apocalypse Now and Colonel Kurtz’s famous lament, ‘The horror, the horror’.

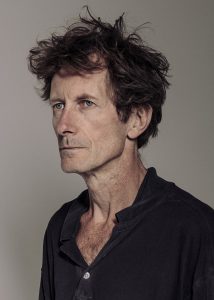

In this exclusive, brief yet fascinating interview, I do my best to get the slightest sense, the mildest hint of what goes through De Sagazan’s head and what makes him the artist he is. Although unsurprisingly, we barely scratch the surface.

Mr De Sagazan. You often talk about culture and fear, and the impact of each. Can culture have a stronger effect than fear?

I think that with age, people like me generally learn to lose interest in or be less affected by fear. Culture and art are the things that motivate and interest me most. As far as I’m concerned, the world isn’t at all screwed up. There are certainly people who make a pact with the devil, i.e. with the economic concept of endless growth and who have no empathy for our planet, but the important thing is to see, each at our own level, how we can act to become aware of our community of interest with our environment.

What does your experience as a biologist bring to your art?

I still have a biologist’s eye, which helps me enormously in my artistic work. For me, there has to be a connection between a work of art and a living organism. When you look at a sculpture, you have to feel its presence, and it has to be like an active fetish.

Your work seems to me to focus on horror rather than beauty – but at the same time, your work has a certain beauty, if that makes sense.

“Beauty is the last step before the terrible.” said the poet Rilke, and here we must understand that beauty is the feeling that everything can change at any moment, and that it therefore lies in this acute awareness of our fragility. There’s nothing mortifying about my work, just a sense of urgency as I try to awaken my eyes and my whole being. Most people only look at my work in the first degree, i.e. that boy who disfigures faces must be a violent, mentally ill type. I have to admit I’m dismayed by such considerations.

What do you think an artist like yourself does, or what effect does it have on the wider political or cultural landscape?

I hope that my images will produce an awakening of thought. I think we’re living in a kind of trivialization of reality, and the aim of art is to shake us out of this torpor. But I’m an artist, not a political scientist.

You’ve said previously that you were religious when you were younger. As you get older, do you ever feel that same longing for religion or divinity coming back?

It happens to a lot of people, including me who’s always been an atheist, but as I get older, I start to feel the need to believe in something. Maybe it has something to do with Freud and his essay “The Future of an Illusion”: as long as we are aware of our own mortality, we can always be attracted by the idea of an afterlife, and so on. Yes, there’s always the return of the repressed, but I’m on my guard. The tragedy of religions is their tendency to want to explain everything, and in this, they become a poison that freezes you in your certainties.

What are your major personal traumas that keep you working and being creative? Or even your own personal triumphs?

I left my father’s faith at the age of 20. It was very hard at first, but then I realized that if life had no meaning, I would give it meaning by finding one, and that gave me enormous energy.

Do you believe in the meaning of “the art of decadence” or “the art of decline”? I like that expression and I think of that when I look at your work.

No, it’s an old concept that comes up regularly, as in the last century with Max Nordeau …

Which philosophers are most important to you, and why?

Aristotle with his key concept that the foundation of the soul is touch. Then came phenomenologists like Merleau Ponty, who went so far as to think that this inner touch would already be present in matter too, hence that wonderful concept of the flesh of the world that I love so much. So there would already be a form of sensitivity in the earth and matter in general.

Which work has been most important to you?

My inaugural gesture was to go and physically enter my work, to cover myself with clay and paint, to become with my body a kind of hybrid between art and reality, or rather to abolish this separation between art and reality so that everything becomes art. Thus was born my performance ‘Transfiguration’. ‘Transfiguration’ is a good example. I wanted to bring one of my sculptures to life, and I’d been working on it for weeks with no results.

What was your life like in the Congo, where you were born? What was it about Central Africa that inspires you?

Central Africa is my cradle in the poetic sense and in terms of my inspiration. What I love about African art, and primitive art in general, is the immediate link with life, in the sense that there is no separation between the two. In the belly of a Teke sculpture, there are pieces of the deceased, and so there is life after death for the deceased and peace for the living. Masks and sculptures are like crutches to help them walk through the “night” and go further in their perception of the world. That’s how I understand art too.

What are your main motivations?

We’re still trying to get out of this collective hallucination that makes us believe that everything down here is normal, that it’s normal to be born, normal to exist, normal to die, and that the world has no mystery left in it. I don’t know, I hope to produce a kind of jolt or awakening to the strangeness of the world, to give it a metaphysical dimension.

Do you have any regrets about the work you’ve created or things you would have done differently with experience?

I [have previously] probably lacked method and always moved forward instinctively. But assurance that has enabled me to push my experiments further and harder.

What projects are taking up your time?

I’m still pursuing my research in painting and sculpture, which still fascinates me. I’m also preparing an opera on Mozart’s Mass in C with Roland Auzet and the Limoges Opera for February 2024.

Mr De Sagazan, anything to add?

I can only answer you with my creations, not with words.

Olivier De Sagazan, thank you for your time.

Visit and view De Sagazan’s work on his official website and social media.